When Mao censored Antonioni

China by Michelangelo Antonioni was different from what the Maoist regime had hoped to present to the West in the 1970s.

China by Michelangelo Antonioni was different from what the Maoist regime had hoped to present to the West in the 1970s.

On March 20th, 2019, the Embassy of Italy in China screened a series of documentaries based on films made by artists from various parts of the world, regarding China in the 1970s.

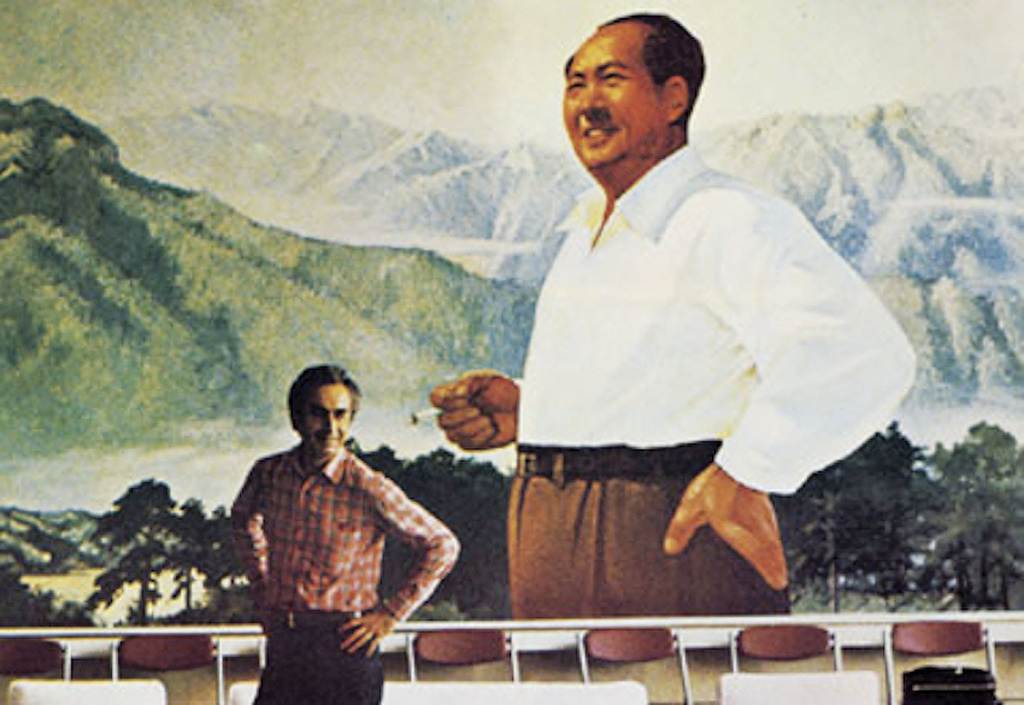

In the first episode, Italian journalist Gabriele Battaglia looks for the people who starred in the censored documentary filmed by Michelangelo Antonioni in 1972, thus trying in a way to restore his good name. The film, titled “Chung Kuo-Cina”, meaning “the centre of the world,” managed to bring Antonioni into a very difficult position. Becoming the most hated man in the country with the largest population on the planet is really something.

“They went to Greece – even when the Colonels were still in power – asking them not to show the film, which is what eventually happened. They went to Germany and tried to do the same. Contrary to the Greeks, the Germans refused. They went to France and tried to do the same again.”

This statement belongs to Antonioni himself, from an interview given to journalist Gideon Bachman in the summer of 1975, and refers to the attempt by Chinese government officials to sabotage the European screenings of his film. The reason was that his creation had a very important “flaw”: He did not glorify Mao and the accomplishments of his regime.

Antonioni began his career with the documentary “People of the Po Valley”, but he is best known for the films “Blow Up” and “The Passenger”. In the 1960s he was booed in Cannes for the “Avventura”, while in the 1970s he was branded in the United States as an Anti-American because of ”Zabriskie Point”.

So, what was the favourite child of neo-realism doing capturing images on a 35mm film in such a distant place?

In 1972, Antonioni was invited by the Prime Minister of China, Zhou Enlai – the second man in power in China after Mao Zedong – to make a documentary on the life of the Chinese after the 1966 Cultural Revolution.

The idea came after discussions between the Italian public channel RAI and the Embassy of China in Rome. The plan was to find a left-wing director who would visit China and undertake to create a propaganda film that would praise the advantages of the revolution. It was one of the efforts made by the Communist regime at that time, in order to open up to the West. It was no coincidence that a little earlier in the same year, US President Richard Nixon visited China after 25 years of non-existent diplomatic relations.

When the Italian director arrived in Beijing, a delegation of state officials waited for him and followed him and his crew closely, for 22 days, all the way to Shanghai. On their voyage, they visited several provinces that had been violently collectivized after the revolution and became part of the socialist “Leap Forward”. Antonioni was one of the first non-Chinese filmmakers to have captured the Chinese hinterland.

The film starts with a busy day in Tiananmen Square, with many close-ups of faces, looks, expressions and movements, under the sounds of a well-known children’s song of the period of the Cultural Revolution.

At the beginning of the documentary, Antonioni admits “we do not pretend to understand China. We just hope to present a collection of people, gestures, customs. (…) Although, in the middle of a political game of ping pong, the Chinese opened some doors for us, they insisted however on preventing us from deviating even slightly from the predetermined schedule.”

Of course, he later manages to escape the watchful eye of his “escorts” several times, enough to film moments outside the controlled boundaries of the state.

A man is practicing tai-chi in a Beijing park (a forbidden practice by the regime), a couple secretly enjoys each other’s company in a corner of the Forbidden City, a birth during which, instead of anaesthesia, the practice of acupuncture takes place on camera, the tracking of “black market” trades – an example of black economy at the time – are some of the moments the viewers are witnessing.

Roland Bart, who had also visited Maoist China at the invitation of the regime itself, says in journals he kept on the trip that “Antonioni did not want to capture the five-story buildings, but the museum-slums, which were preserved only to indoctrinate children to the notion of class struggle.”

On the other hand, anthropologist Kathleen Kuehnast, despite the fact that she has described Antonioni’s approach as quite sincere, nevertheless comments that “it sometimes portrays images of intense exoticism, by interpreting people, landscapes and objects in the light of a Western filmmaker who records the “other”, the primitive.”

When Antonioni completed the editing, the film’s duration was 217 minutes. “The first persons to see the movie, apart from my associates, were some representatives of the Chinese Embassy in Rome.”

“Mr. Antonioni, they told me, you have a very affectionate look for our country and we thank you for that… I do not know what happened afterwards. I have no idea why they changed their minds,” Antonioni admitted in an interview.

A massive campaign against the Italian director began, from Chinese magazines, newspapers and critics who had not even seen the film, in order to defame him. Even Italian Maoist students protested at the Venice Film Festival during the screening of the documentary, to show their dissatisfaction.

Listen to the Party, the Party knows best

Make Antonioni bite his tongue

The red flag will fly from the East to the West

The lyrics above are from a children’s song taught in every school at the time.

It is said that the instigator of this targeted attack was Mao’s wife, Jiang King, which needed an occasion to undermine the Prime Minister, Zhou Enlai, who had begun to gather enough power. Zhou Enlai was the one who invited Antonioni to China.

“We had given so much love to this film. The editing process alone took six months,” said Enrica Fico, the wife of Antonioni who had worked for the film as an assistant. “It killed him to think that our country considered us as enemies,” she had said.

The film “Chung Kuo-Cina” was banned for almost 30 years. In 2004, it was publicly screened at the Beijing Academy of Cinema. But it was already too late. Michelangelo Antonioni was already very subdued due to his advanced age and he could not attend. Otherwise, as his wife had said, he would have liked to see what the new generation of Chinese people would think of his film. “Because, we all love the Chinese people and so do I,” as he said in the past.

Before you go, can you chip in?

Quality journalism is not of no cost. If you think what we do is important, please consider donating and becoming a reader who makes our work possible.