This story was updated on October 27, 2021, two days after its publication.

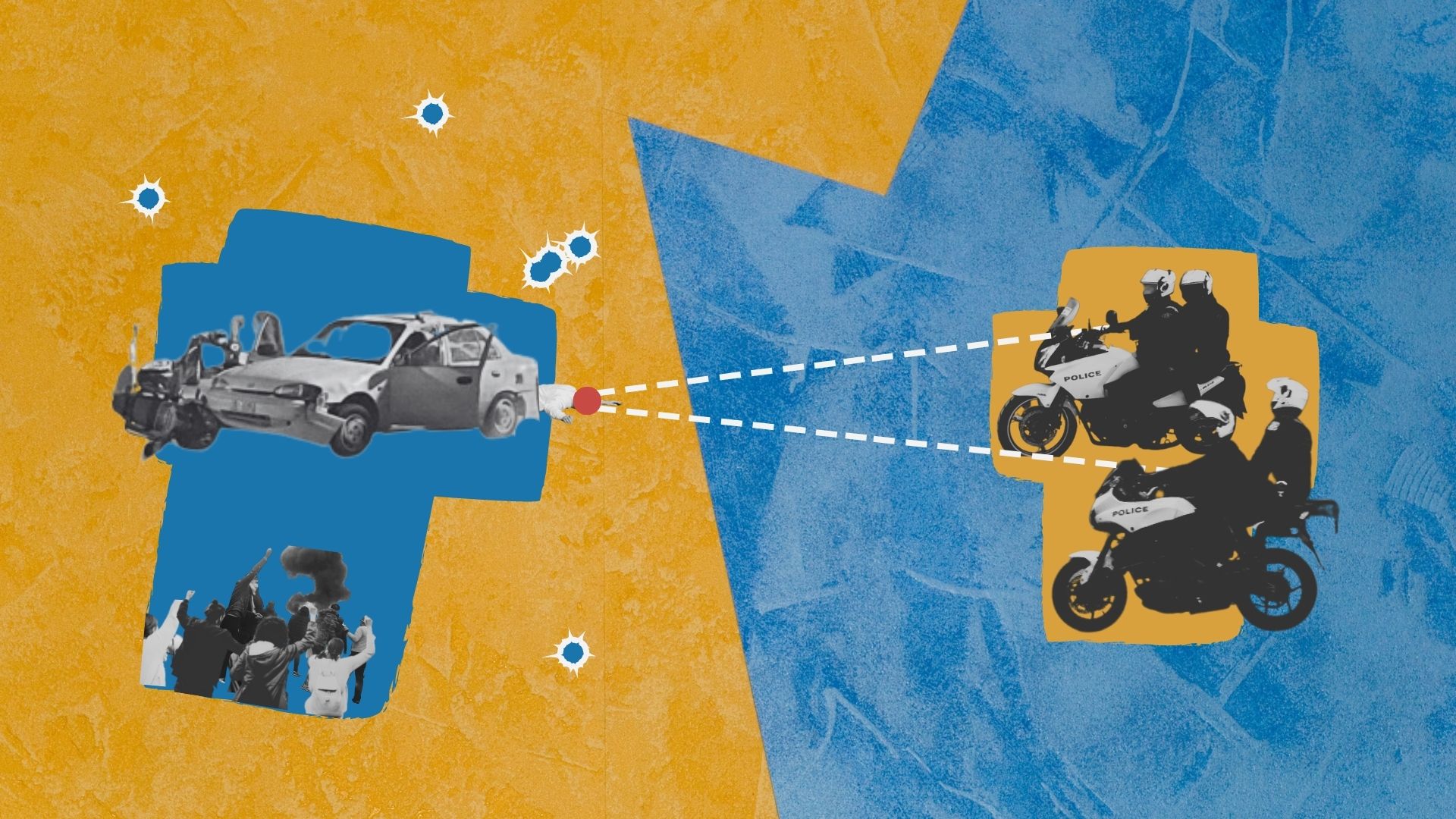

The murder of Nikos Sampanis in Perama, west of Athens − in the early hours of Saturday, October 23, under a storm of gunfire by the DIAS motorcycle squad of the Hellenic Police − raises serious questions about whether the use of fatal violence was legal.

According to witnesses and videos that have been made public, the three people in the car were unarmed. In one of the videos, the police can be heard saying that none of them are injured, refuting the statement by the Hellenic Police HQ of Attiki, which claimed that in their attempt to escape, the perpetrators rammed five police motorcycles and injured seven officers. The policemen shot and killed one man, severely injured another who was taken to the hospital, and the other escaped.

It was initially reported that the person who died was the driver of the car. However, the passenger who escaped, a 14-year-old minor, surrendered to the authorities on Wednesday, October 27, 2021, and claimed that he was driving the car, and that he reversed the car into two parked motorcycles only after the policemen started firing and had killed his friend. Communications over the police radio during the chase, between the officers involved and their controller (which have been made public), reveal that the policemen in pursuit had identified the passengers in the car as members of the Roma community.

The prosecution arraigned the seven officers who participated in the pursuit, who are being held at Hellenic Police HQ, to appear at an investigative hearing on Wednesday, October 27. The Minister of Citizen Protection, Panagiotis Theodorikakos, released an official statement asking the Chief of Hellenic Police, “to proceed urgently with a disciplinary investigation,” and, “a full operational evaluation of the action of the Hellenic Police,” before he visited the seven officers being held at the Hellenic Police HQ, in order to “show support”, as he stated on social media.

This is the fourth case in the last month, of police officers using their weapons under similar circumstances. In all four cases, police fired on vehicles that did not stop for inspection, even though the rules of engagement prohibit the use of a weapon against a person who refuses to stop and flees. Police involved in the incidents (including the most recent events), claim they were forced to use their weapons because their motorcycles were being rammed by the perpetrators.

The Makaratzis case

The questions about the use of deadly force during the car chase in Perama, however, bear great similarities to those that were raised in a particularly important case on the same issue − the case of Makaratzis v. Greece, which was tried at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), in 2004. Nine years earlier, in September 1995, police had attempted to stop a car that was driving over the speed limit and had run a red light near the US Embassy in Athens. The driver, named Christos Makaratzis, did not stop. A chase ensued, in which − under the constant and stormy gunfire he received from police revolvers and submachine guns − he collided with two cars and escaped from five police blockades, before finally stopping at a gas station. Makaratzis was shot in the leg, arm, buttocks and chest, but survived.

The disciplinary investigation by the Hellenic Police involved as many police officers as they could locate, because according to the police, several officers had left the scene before their weapons could be inspected. As a result, the investigation could not match the bullets that injured Makaratzis or were found in his car to specific weapons. The prosecutor’s office put seven police officers on trial, on charges of dangerous bodily harm and use of weapons. In 1999, the three-member Athens Court of First Instance acquitted the police officers.

Although in its ruling, the ECHR accepted, as did the Greek court, that the use of a weapon under these circumstances may be lawful, it expressed surprise at “the chaotic manner in which the police used their weapons”. The court ruled that the Greek authorities had violated Article 2 (“right to life”) of the European Convention on Human Rights by “failing to provide citizens, especially when (possibly deadly) violence is used against a citizen (such as in the case of the plaintiff) with the required level of guarantees and to prevent the real and immediate danger to life which they knew was likely to arise, even only in exceptional circumstances, in police operations involving the pursuit of suspects.”

In addition, the ECHR condemned Greece for the fact that it did not conduct an effective investigation into the incident and awarded compensation of €15,000 to the victim.

The Sidiropoulos-Papakosta case

The Makaratzis case was the main lawsuit in a group of ECHR cases involving instances of illegal violence by Greek law enforcement and the failure of both disciplinary and judicial proceedings to investigate them effectively, in a way that helps prevent further incidents. Gradually, other cases were added, which were more characteristic, perhaps, in relation not only to the illegal violence itself but also to the immunity that is essentially criticised in these rulings, as in the Sidiropoulos-Papakostas v. Greece case.

On the night of August 13, 2002, two police officers arrested 17-year-old Giorgos Sidiropoulos and took him to the Aspropyrgos police station. He was driving a motorcycle without a license and when asked if it was his, he replied that he had found it in a field.

While interrogating him, the duty officer appeared, holding a black device. He touched the device to Sidiropoulos’ chest and near his genitals. The detainee felt an electric current pass through him and became paralyzed.

Several hours later, other police officers arrested 20-year-old Giannis Papakostas, who was driving a motorcycle without a license, and took him to the same police department.

The duty officer again brought his device and touched it to the detainee’s back and near his genitals. Papakostas fell to the floor in severe pain and could not get up.

Sixteen years later, in 2018, the ECHR ruled on their case. The court found that the Hellenic Police, in the Formal Administrative Inquiry (EDE) which they carried out, concluded that the said officer was only responsible for the unlawful possession of a “portable transmitter-receiver device” − as he did not have the required permission from the Ministry of Transport and Telecommunications to carry it. He was given a fine for €100 and the case was filed away. As a result, the officer remained in service, was promoted to the rank of sergeant and retired from service at his own request, in 2010.

The ECHR also found that 12 years had passed since the beginning of the pre-trial investigation until the end of the second instance criminal trial. Finally, the court found that although the Greek justice system found the voluntarily discharged officer guilty of torture, it punished him with one of the lightest sentences permitted by law: five years in prison, redeemable for €5 a day. In fact, the court took into account the financial hardship of the officer, and allowed him to pay the amount in 36 installments.

The ECHR awarded €26,000 in compensation to each of the victims, and ruled that “such a sentence could neither be considered appropriate, nor prevent the perpetrator or other government officials from committing similar offenses, nor be considered fair by the victims”.

Regarding the EDE that was filed, the court noted that the police officer continued to serve “for eight years after the events in question, without suffering the consequences of his actions” and that due to the length of the criminal proceedings, the EDE could not be revisited after his sentencing, as the law provides, while the police officer “also received a promotion, with all the moral and financial consequences that it entails”.

In this context, the ECHR ruled that “the lack of rigor in the application of the penal and disciplinary system, as in this case, does not prevent law enforcement agencies from committing unlawful acts, similar to those which the plaintiffs reported”.

Monitoring by the Council of Europe

Member states of the Council of Europe are committed to implementing the decisions of the ECHR, not only in terms of compensation awarded but also in terms of improving legislation and administrative procedures identified as problematic. To this end, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, (the relevant body comprised of the foreign ministers and supervising the implementation of the decisions) asked the Greek authorities to implement a series of measures to deal with illegal violence.

Some of these measures had already been taken. For example, the outdated law on the use of weapons by the police, which was introduced in 1943 during the German occupation and was still in force at the time of the Makaratzis case, was modernized in 2003. Critical issues, however, such as the reform of torture legislation and, above all, the establishment of an effective mechanism for investigating complaints that would address the chronic inadequacy of internal disciplinary proceedings, remained pending, which put the Makaratzis group’s cases under “enhanced supervision” − which is reserved for cases of systemic problems that require structural solutions.

On September 16, 2021, the Committee of Ministers decided to close some of the cases in the Makaratzis group, evaluating the individual measures that have been taken, such as the disbursement of compensation. In relation to the general measures intended to address systemic problems, the relevant memorandum points to a number of improvements, such as the introduction of the Ombudsman Mechanism in 2016 and its continuing development in 2020; the new Disciplinary Code of 2019; the reform of the law on torture in 2020, etc.

It also gives weight to the apology expressed by Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis last March, after the events in Athens, to the victims of police violence − something that has been a constant request of many victims and especially those who, due to statute of limitations, could not bring new charges against their perpetrators after being vindicated by the ECHR. The memorandum also highlights the prime minister’s vow to enforce police accountability.

It is therefore, if nothing else, interesting that at a time when a number of cases are being closed thanks to supposed improvements in the regulatory framework and the prime minister’s public vow in parliament, there’s an incident of deadly violence by police officers which is strikingly similar to previous cases. The reasonable question, then, is whether these improvements, as well as the promises, translate into actual changes in police behavior.

The Committee of Ministers, however, does not consider the closure of cases reason for the lifting of “enhanced supervision”. On the contrary, the committee maintains the observation of a new group of cases under Sidiropoulos-Papakostas v. Greece, and underlines that the closure of the cases does not “influence, in advance, the assessment of the general measures needed to prevent the recurrence of police violence and the absence of effective investigations into unlawful actions and deaths…”.

Endemic impunity

In every instance, the cases of police violence that come to trial at the ECHR are relatively few, either in relation to the number of complaints that occasionally see the light of day or in comparison to what is recorded by Amnesty International. The assessment of the problem as “systemic” by the Committee of Ministers, however, is certainly supported if one refers to the most serious cases in recent times, involving police officers.

It is therefore not unreasonable that PM Mitsotakis’ vow and the announcements for disciplinary and criminal investigations are not enough to create a sense of security for the clarification of the incident in Perama or for the issue of unlawful police force in general. After all, that’s what the verdicts against Greece, reveal: that apart from the incidents of violence themselves, both the EDE and the Greek judiciary systematically fail to act in a way that effectively investigates and holds those accountable for arbitrary police behavior, creating a prevalent culture of impunity.

In Part Two we will further examine the problems of the internal disciplinary procedures of the Hellenic Police, as well as the attempts to establish review mechanisms that have been made by successive governments to date.