* Names of people and locations may have been changed.

Keita is from the Ivory Coast and has been living in Athens since 2010. As a minor, he decided to leave his family and pursue his dream to play football.

But instead of fulfilling his dream of having a career as an athlete, he found himself working in a factory with others his age, in an eastern Mediterranean country.

He remained there until he could save enough money to pay the traffickers, and begin a difficult, uncertain journey − crossing the borders of various countries and trying to reach his final destination, France.

For a time, he believed that his stay in Greece would be temporary, and would not give up on his initial plan of reaching the country he wished to live in permanently.

Ten years later and after an unequal fight with Greek bureaucracy to get his residency status in order − a battle which tested the limits of his sanity − Keita has received his three-year residency permit and now works as a translator at Caritas Hellas, and also is planning to study to become an athletics coach.

This is his story.

In Keita’s words

I came to Greece in 2010, when I was about 17 years old. I don’t remember the place where I arrived that well. What I do know, from what I’ve heard, is that I definitely passed through Thrace, on the border with Turkey.

Before that I was in an eastern Mediterranean country. I went there from the Ivory Coast, where I come from, to play football. I met a woman who told me, I will take you there and you will play football. I was young.

When I got there, she told me, you can work here. You will work for six months, you will give me the money, and for the next six months what you earn is yours. This is what I was told, even though my visa and ticket were paid for by my parents. But I knew some older kids who were also from my country, so I left her and went with them. We worked from seven in the afternoon until seven in the morning at a factory that makes bottles for Coca-Cola. If we had known from the beginning that things would have been like that, my parents wouldn’t have let me go.

The kids I stayed with were good kids in the beginning. And then, you know, when you’re trying to move on, to find somewhere else to go… Everyone wants to find something better for themselves.

I saved some money and, I think after six months, we were looking for traffickers who could help us cross to Syria, and from there to Turkey. As we walked through the mountains between the two countries, shots were fired. Turkish soldiers had spotted us and were chasing us. I became separated from the group and found myself running in another direction. I was caught and taken to a military base, just me, there were no other refugees. They didn’t know what to do with me. The soldiers gave me a nickname, meskín, which, in Arabic means someone who is poor and unfortunate.

Later I got to Istanbul. The traffickers told us, you take a bus, it drops you off somewhere in the jungle and from there you continue on foot. And you’ll reach somewhere, you will see the Greek flag on the license plates of the cars, and then you will understand that you have to stay there, and the police will come to pick you up. So, we arrived and the police came. They took us to a place that looked like a prison. There were a lot of people and they put us all together.

There, if you don’t cause any trouble and you have money, you’re allowed to leave in three days. If you don’t have money, you stay. If you had €50, the police would send you directly to Athens, if you had €20, you would go to Macedonia, and from there you would come to Athens.

There was a bus from the jail. I had nothing with me. In Turkey I was in jail with some other kids. And we were still together, and they had money and parents who could send them money, and they gave me €20. And so, I went to Macedonia with $100 on me. I arrived on a Sunday. The banks were closed. In the evening I gave my money to a man I met from Nigeria and he exchanged the dollars for euros, and I took the train and finally arrived at Larissa Station.

So, I found myself in Athens, and from others, who had already been through all the procedures, I found out what I had to do. I went to the GCR (Greek Council for Refugees). It’s the only thing I remember from when I got here. We went there for our papers, and you applied as a minor if you wanted to go to the hostel. After I completed all the necessary paperwork there, I was sent to the Department of Immigration on Petrou Ralli St. It’s the worst place you can think of in this world.

The truth is that the first time I went to GCR I didn’t even know what asylum was. I didn’t know I had to tell my story somewhere. When you get here, someone may tell you, don’t say that, say this, however the information you are hiding may be the right thing to say, and what you are being told to say may be wrong. Some people, who have lived in Greece for many years and have experience with all of this, might ask you for money for them to give you information.

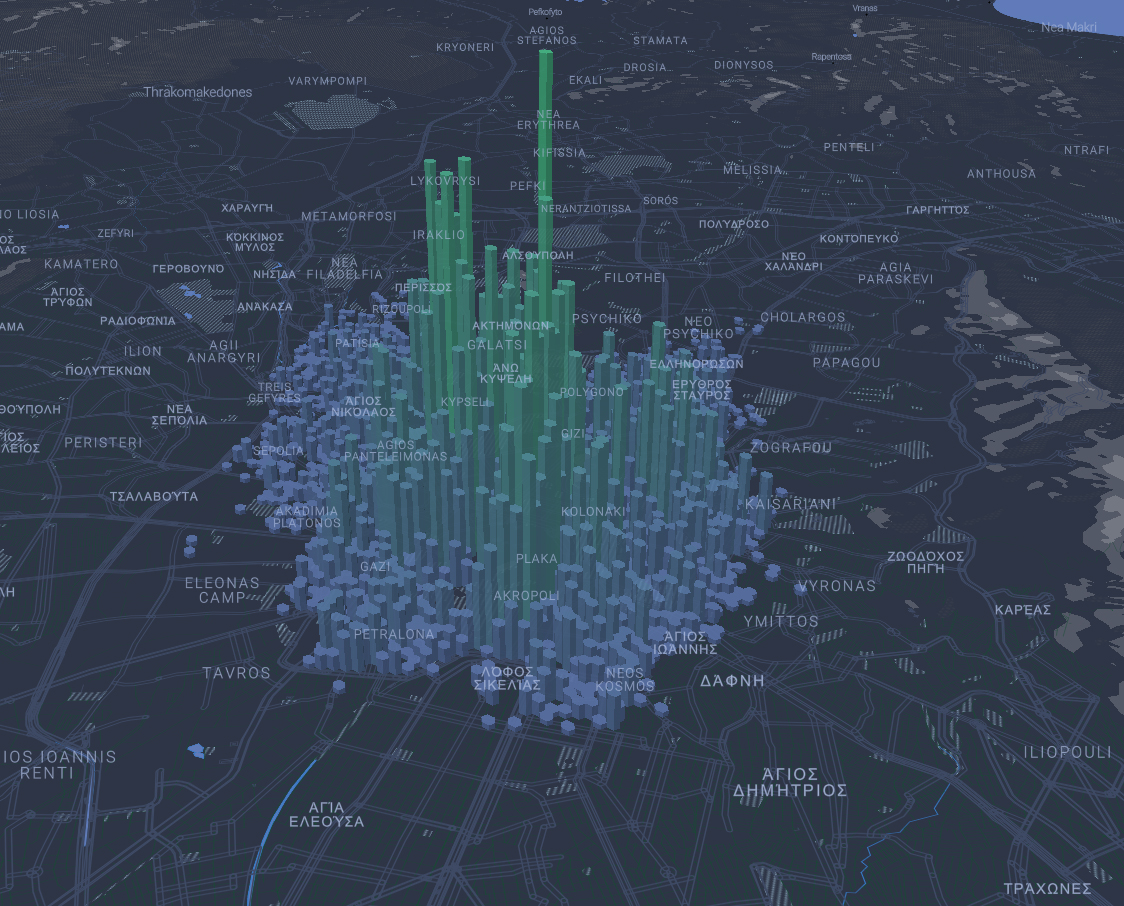

When I came I was out for a year… Not on the streets… I lived in a house with other men. We lived together, about 18 people and we each paid €13 – €15 a month. The house was rented by a guy who knew how to speak Greek, so it was easier for him to arrange everything. The place was on Drossopoulou St, off Patision Ave.

The first day I got there and saw all the people living there, I thought, how can this be? It was very difficult to comprehend. Wherever you went there were people. Things weren’t good in Africa either, but so many people living in one house? I grew up in a house that was very crowded, but it wasn’t like that, everyone had their own space. It was difficult, very difficult. But I was not afraid. Not at all. Because all the guys were from Africa, there were other kids we had met before, before we got here. I wasn’t scared, I just didn’t expect it all.

At one point I didn’t have any money, and so they asked me to leave, and I went to the GCR again to apply for housing at the hostel. Look, I didn’t want to go to the hostel because I definitely wanted to leave Greece. To leave illegally. So, I thought if I lived at the hostel, I wouldn’t be able to leave. But I had to go. Where else could I have gone?

They didn’t offer housing to single men back then. They don’t offer it now either. Who will care for them? I was told that hostels were available if I wanted to go, and I told them yes. I applied and one day they called me and told me to gather all my things and go there. First, I asked where they would send me, because I wanted to go somewhere far from Athens. I knew some other guys who had gone to Volos or Patras and they had even found work there, and they managed to leave Volos and move on. I wanted to do the same. I definitely wanted to go to France. You know, breaking the law, in this case, is a good thing, because you must do it in order to survive.

So I asked, where are you sending me? They said they wouldn’t tell me. And in the end, the hostel was here in Athens, in Dafni, at a hostel of the Apostoli. I went but I didn’t want to stay. But I said since I have no money to pay, I’ll stay there and try to do something else, and if I find an opportunity to leave, I will leave.

I was in the hostel for three days, I was tested, everything was fine, and then I was told I could go to school if I wanted to, so I wouldn’t be stuck at home. It was a good opportunity for me, because in Africa I didn’t go to regular school, so I accepted. I was enrolled in the 2nd year of middle school, at the intercultural school. For the first three months, I only went to have fun, of course, so I wouldn’t be stuck at home. But then I liked it and said I would stay in Greece. It was a very difficult time for me. One minute I wanted to stay, the next I wanted to leave. I didn’t know how to leave but I didn’t see a future either. And so I decided to stay.

I finished middle school and it was time to transfer my papers to high school, but at that time I was very down. Psychologically, I was down, and I had asked them not to transfer my papers because I was going to leave. They asked me, where are you going? I said, I will try to go somewhere. However, I do not want to stay here. But again, in the end, something inside me told me to go to school and then if you want you leave, and so I told them I’d go to high school. And so the first year passed.

During the second year I met a girl. She was born in Greece but her parents are from Albania. We were classmates, and sat together in class. Meeting her gave me the courage to stay, to see what would happen. And so little by little I managed to finish high school.

When I met my girlfriend, it was a very difficult time for me. On every level. First of all, when I lived at the hostel, we went to school but we were hungry. It’s the truth. Because the food they gave us was not enough. So I had to spend money every week to eat. The Africans who didn’t live in hostels, collected money and cooked every day, each night. Each paid €3.50. I would leave the hostel, go to their place, eat and then go back. It was the same place I had stayed before I went to live at the hostel.

I can’t forget everything I’ve been through. As soon as I finished high school, I got a job at Caritas. I was told at the hostel that when you finish school you will find work. And that’s how it happened. I finished school, got a job, did everything right. Even in the most difficult situations, I chose to do the right thing. I wondered, why go through all this? I wanted to die. I sat alone and said, if there is a God, let him feel sorry for me. I have done nothing wrong in my life.

My girlfriend helped me psychologically and made me believe in myself. For example, she was the one who told me, I swear, as soon as you finish school, things will be much better for you, I know that even if you don’t realize it. And inside I was wondering, is she telling me this so I won’t drop out of school? And as soon as I finished school and got a job, she said, see what I was telling you? And when I later managed to rent my own apartment, she told me again, see what was I telling you before?

I laugh because if I said that I had a hard time with my papers, it would be an understatement, if there is another word to describe it, I would tell you, but I don’t think it exists. I managed to get my papers after ten years. I waited almost five years for the first interview and then about five more years for the second interview. And in the meantime, rejections, objections, appeals… Now I’ve had my residence permit for three years. When the decision was made, I didn’t believe it. I would ask my lawyer again and again if he was sure I got it.

You know in the beginning, when you start, you think it’s like the way it is in your country, you share everything with people and you consider them all your brothers, but that’s not exactly the case. I would hear someone speaking French and I’d think, oh I found someone from my country, and because I missed my country, I trusted people very easily. Now I’m more hesitant. And strict when necessary. I’ve learned how to say no. Before I couldn’t, do you understand? And it’s very important to be able to say no. I’m not saying this for sure, but maybe it all made me become more guarded with people. Or so it seems. Some girls would say he’s anti-social. But that wasn’t true at all. I like to be alone. I’m just hesitant and I don’t trust people easily.

During the time I was going from one country to another I had no contact with my parents. One day, when I was in prison at the border, someone gave me a phone card.

He said to me, you don’t eat, you don’t talk, you don’t say anything. Have you talked to your parents?

No.

I have a card, he said to me. You can make a phone call. Do you have the number?

Yes.

And so I called. I talked to one of my brothers and he asked, what happened? We’re scared, we don’t know where you are. And I said, yes I know but I’m in jail, they’re trying to send me back, but we’ll see. I don’t know anything yet.

Until I arrived in Greece, however, I had not communicated with them at all. Now we talk almost every day. I haven’t seen them in ten years.

Journalist’s Notes

“I didn’t know I had to tell my story somewhere.”

To obtain refugee status, asylum seekers are asked to narrate their life history as well as the way in which they understand the world and their relationship to it, in legal terms, fulfilling the expectations of the role of a refugee. This narrative must be “credible” − meaningful in a Western and European context of understanding − and present a series of events with a logical sequence that lacks contradictions. It is the job of the examiners to distinguish “truth” from “falsehood”, “consistency” from “inconsistency”, and differentiate the “genuine” refugee, one who has the right to (and deserves) our protection, from someone we have no legal or moral obligation to protect.

This presupposes that asylum seekers are subjected to long, [simple_tooltip content=’In some cases, the opposite is true. With the implementation of the new legislation (4636/2019) of the New Democracy government to expedite the asylum application procedure, there has been a sharp increase in objections from applicants and people active in the field of asylum interviews – who claim that the interviews are completed in just a few minutes.

For example, in a case involving a Senegalese asylum seeker, whose interview is said to have lasted just five minutes, his application was rejected on the grounds of “non-cooperation with the authorities” although the interview could not take place as required by law, because of the lack of an appropriate interpreter, thus inability to communicate. However, reports of similar incidents involving unaccompanied minors have been reported since 2008, when the Department of Immigration and Asylum on Petrou Ralli St was still the main service processing asylum applications.’]exhausting and complicated hearings[/simple_tooltip] during which they must prove the “authenticity” of their story.

Thus, the asylum hearing and decision-making process suggests and legitimizes certain regimes of truth and relationships of power, regulating who is entitled or not to be granted refugee status and the protection under international law. In this system, “truth” will emerge by submitting a mass of evidence and the retelling of detailed information, including dates, numbers, places, names and people. And, of course, all of the above can easily be rendered useless, without the applicant’s ability to submit this information in a way that will ultimately compose a compelling and authentic narrative.

When Keita arrived in Greece in 2010, a minor at the time, he did not know he had to tell his story somewhere. But very quickly, and often using and evaluating with his own judgment, the experiences of those who were in his place before him, he learned to tell his story. Refugees learn to conduct themselves as refugees, and suppress other personality traits. They must assimilate and implement a specific narrative of persecution, even if it is difficult for them to talk about their experiences. They learn to tell their story of exile to the Asylum Service, to lawyers, to interviewers, to NGO workers, journalists, researchers and solidarians.

Thus, the stories of people fleeing their countries in fear of violence, or those who have experienced violence, may quickly be transformed and rendered as narrations of asylum – and the decision-making process for granting refugee status depends on these accounts. And this may ultimately lead, on a large basis, to understanding the refugee experience through the perspective of a legal framework which dictates the conditions for narrating that experience.

However, obviously familiar with telling his life story, and despite the awkwardness of the first meeting, Keita knew how to choose between what needs to be said and what should remain “off-the-record”, always actively engaged in the way he manages and negotiates his story, as a young man who arrived in Greece ten years ago in search of international protection. After all, the afternoon I met him, he showed up to tell this story. But even so, the refugee experience is often not a rigid and indifferent narrative, but rather an opportunity for refugees to be actively involved with others, from which a variety of life stories emerge.

Survival strategies

1. The “protective care” of minors in prison cells

The extremely precarious conditions in which a significant number of unaccompanied minors are forced to endure, inevitably lead to impasses and using survival strategies that seem to be “the lesser of two evils”. One such example is seeking secure housing by sheltering minors in “protective custody.”

The estimated waiting time for an unaccompanied minor to be placed in adequate accommodation at the time of application is about seven months. In practice, this means that as long as the request is pending, the minor remains in temporary accommodation, or on the street, exposed to dangers. There are many cases of minors who, no longer able to endure and manage life on the streets, choose to be referred to “protective custody” until accommodation becomes available. In this way their request for housing takes precedence, thus reducing the waiting time.

When a minor appears before the Greek Council for Refugees, as in the case of Keita, the process of applying for safe accommodation moves in parallel with legal assistance and representation before the authorities in the asylum procedure.

According to sources in the field, the female minors are usually more fortunate than the males, because if they happen to be identified by the police, they are more likely to be temporarily transferred to the Children’s Hospital, instead of ending up in a cell in a police station, or at the Amygdaleza Detention Center, as is the case with boys. The girls will remain in a special wing of the Children’s Hospital until appropriate housing becomes available.

According to the most recent figures (May 2020) of the National Center for Social Solidarity (EKKA), 956 unaccompanied minors out of a total of 4,898 (estimated number) are living in unsafe housing conditions, such as in apartments with others, are squatters, are homeless, and often move from one type of accommodation to another.

In the enforcement of the so-called “protective security” policy of the authorities, 274 unaccompanied minors are being held in detention centers of Police Departments and Border Patrol Departments, in Immigration Management Units and in the Pre-Departure Detention Centers such as Petrou Ralli and Amygdaleza, and also at the Reception and Identification Center of Fylakio, the only center in the country that essentially functions as a contained housing facility, which prohibits residents from leaving the center.

Increasing allegations have been circulating, claiming that unaccompanied minors are being held with adults and criminals, similar experience that Keita shared with me. Incidents involving female minors have also been recorded at the Department of Immigration and Asylum on Petrou Ralli St, which does not have a juvenile wing. Thus, when minors are transferred to the facility, they are held in custody with adults, which has led to repeated allegations and condemnations by the European Court of Human Rights.

2. Staying together

Living with people of the same ethnic background, even under extremely difficult circumstances, can provide, even temporarily, a sense of familiarity among refugees.

“I heard someone speak French and I thought, Oh, I found someone from my country,” Keita said at one point during our discussion, “and because I missed home, I trusted people very easily.” For Keita, as well as for most unaccompanied minors living in unstable conditions, living with “people from back home” provides a support system.

Try to imagine yourself among a group of people, where no one can understand your language, and you can’t understand their language either. Certainly, there will be confusion between you, and the two sides will probably try to manage by inventing different ways of communicating. This of course presumes that both sides want to make an effort to understand each other. But even if the willingness to communicate is mutual, it is very likely that at some point it will all become tiresome and you might feel uncomfortable.

Now imagine yourself among the same group of people, but this time you are in the middle of an extremely critical situation, where you must use the information that you can manage to get from the group to make decisions about your safety. And while others in the group share this knowledge with each other, you are unable to understand the situation and the scope of the dangers to which you are exposed. In this case, you may need to leave these people in search of a new group that you will feel more secure with.

You stay close to those who speak your language, not because understanding a common language offers familiarity. Or rather not only for that reason. You will soon realize that language primarily means security. The ability to communicate in a common language means access to important information which is used to organize the daily life of an unaccompanied minor, who arrives alone or with others the same age as him, in the unknown city of Athens and has no place to go. Living in a shared apartment with other minors and adult men will temporarily serve as a safe haven.

3. Under the radar

Greece was not the final destination of Keita’s journey. Crossing borders from one country to another, his goal was to live and work in France.

When he reached Greece, and during his time here, his basic intention was to find a job which would allow him to save money to pay a trafficker, so he could leave. In any case, before 2015, Greece (for a large number of people who were waiting at the border but remained trapped here), was not a destination, but a temporary stop on the journey, until people could fulfill their dreams and go to a central or northern European country.

And for Keita to be able to continue his journey, he had to stay under the radar of the police and the NGOs, even when it is the NGO which allowed him to improve his situation. His accommodation at a safe shelter, Athens’ urban network, and his decision to invest time in his education here, meant that his stay in the country was extended, as his final destination was initially France. Everything merged to eventually contribute to the change in his original plan.

When he could no longer continue to live “under the radar”, he sought safe accommodation in the hope that he would be sent to a port city, such as Patras or Volos, to make it easier to leave. Hidden in a truck, like many others had done before him, he would have boarded one of the ships which travel to Italy, and from there continue on to France.

Since the early 1990s, the port of Patras has served as a major gateway for immigrants, mainly from Albania, to central and western Europe. Later, the war in Iraq, the mass persecution of the Kurds by the Turkish state, and the American invasion of Afghanistan, led to a significant increase in population movements.

The ports of Igoumenitsa and Patras have attracted thousands of undocumented immigrants, and has served as a relatively safe sea route for their passage from Greece to Italy, and from there to the countries of western Europe.