It should be a special day for Jamal. Following an exhibition of children’s artwork at MuCEM in Marseilles (Museum of Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean), the drawing he had created with the help of his friend Ahmad, made the front pages, on March 13, of one of Europe’s most important newspapers, Le Monde.

When he was asked about his drawing, Jamal said he felt sorrow and anger when he drew a picture of war-torn Syria – and he felt the same way when he was told that his drawing managed to travel to such a faraway place.

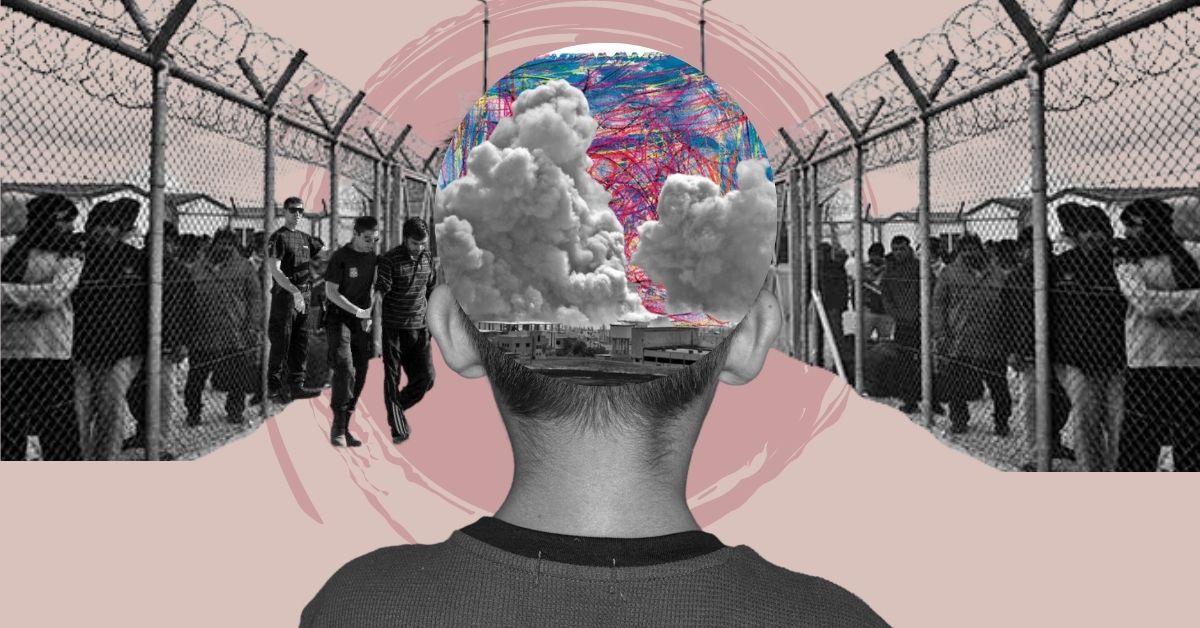

“They told Jamal the news. And he replied: I’m just drawing what the conditions here are like, and I will continue to draw what I see, that I’m in a prison,” said Hamam Widad, the boy’s mother.

“And he told them, I don’t want anything from you. Nor am I happy that my drawing has traveled to another place, while I’m still in prison.”

From regaining his self-confidence…

Jamal is a child who has spent half of the 12 years of his life on the street. When they were forced to leave his hometown of Aleppo, he was so young that he doesn’t remember when it happened − “my mom knows when” he says.

Jamal was six years old when he left Syria with his mother and two siblings, 14-year-old Hala and 8-year-old Yasif. It’s been almost two years since they arrived in Kos in an inflatable boat from Turkey. Initially, they were housed at the Reception and Identification Center of the island, which today has a capacity to host 816 people.

There, according to people who had daily contact with the family, Jamal began to find his footing: he started school at the KEDU Education Center run by the NGO Arsis, he made friends and regained his self-confidence. At that time, on the tenth anniversary of the beginning of the war in Syria, children were asked to create drawings for a competition organized by the United Nations and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

“The day we were asked to make drawings about the war, I did not feel well,” he later said. But his friend Ahmad, who was on the island after fleeing Palestine with his brother, asked Jamal if he would help him create a drawing.

“The way we just threw the colors on the paper made me feel much better. Syria has been destroyed now, nothing is in its place. Just like the colors in this drawing.”

…to being detained

Jamal had begun to regain confidence in his surroundings, but this was abruptly interrupted five months ago when his mother’s appeal for family reunification with their father in Germany was rejected, and they were transferred to the Pre-Departure Detention Center (PROKEKA) of the island.

“We are in a closed space that’s like a prison,” Widad told Solomon.

“We live in a container with my children and another woman who is here alone. We are not allowed to leave PROKEKA at all. The food is very bad, but we have no money and we are forced to eat what they give us, even if it is past its expiration date. Due to the conditions here, my children now suffer from psychological problems.”

Under these circumstances, Jamal gradually drifted away from the environment he had built around him.

Online classes are offered by NGO Arsis so that children in detention conditions on the island won’t completely lose contact with the school and the outside world. But when Jamal stopped attending the online classes, his mother told the teachers of the organization that her son refuses to participate “because he no longer finds any reason for it”.

“Mom, will we stay here forever?”

“It is a crime to keep children in here,” says Widad.

Her children spend most of their day in the container. They wake up in the morning, eat their breakfast, and go out to play. But without anything to do, they end up arguing with each other.

Widad says her children are scared. A few days before our telephone conversation, Macky Diabete, a 44-year-old asylum seeker from Guinea, died at PROKEKA. According to testimonies, he suffered for days in horrible pain, before dying from a bowel obstruction.

“When that man died they asked me, Mom, if you die, will we stay here forever?” Now, however, she is also afraid for her children.

“They ask me a million times if we will get out of here. Many times they tell me it would have been better if they had died in Syria than to go through all this suffering here. Other times they tell me that it’s my fault, because as their mother, I brought them here, in these circumstances,” she says.

And, she adds: “Many times I catch Jamal wanting to hurt himself to get out of here. I’m afraid. I pray to God to help us because we go to sleep depressed and wake up depressed.”

The “gray zone” of PROKEKA

The following pre-departure centers operate in Greece today − two in Attiki: Petrou Ralli and Amygdaleza; one in Corinth, Drama (Paranesti), Xanthi, Orestiada (Fylakio), Samos, and Kos.

The people living behind the barbed wire in these centers are not facing charges for any criminal offenses. The PROKEKA centers are for the administrative detention of persons: in essence, people who are not recognized as having the right to stay in the country and are held there until they are deported or, in reality, are released with a document stating that they must leave the country.

However, contrary to what is true in the penitentiary system, the operation of PROKEKA is in a gray zone.

“If, for example, there is a criminal procedure against a person, and he is a prisoner, then he serves his sentence under certain specifications, having certain rights, and knowing how long the sentence or procedure will be,” explains Achilleas Vasilikopoulos, coordinator of the NGO Arsis’ education centers.

“But in administrative detention, these conditions do not exist.”

Nobody knows how long they’ll be there

As in the case of Widad and her three children, no one in custody knows exactly how long they’ll have to remain there.

After all, the very circumstances of asylum seekers’ transfer to the detention centers differ. Currently, at the centers on the Aegean islands, for example, there are both asylum seekers who were transferred there after their application was rejected in the first instance, and others whose appeal has been rejected, such as Jamal’s mother.

But at PROKEKA, there are also people who were transferred there immediately, after their registration, that is, before a reply was even issued to their asylum request.

Greece has been repeatedly condemned by the European Court of Human Rights for the conditions prevailing in the country’s PROKEKA, which has been highlighted in reports by the European Commission for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT), the independent European body that inspects detention facilities.

At the end of March, the day after Diabete’s death at the detention center on Kos, a 27-year-old Kurdish man seeking asylum committed suicide at the detention center in Corinth. He had been there for 18 months and, believing that he would be released, was informed that his detention had been extended. Others who were in custody with him at the time, said the decisive factor was the uncertainty as “no one informs you when you will leave”.

Children deprived of access to education

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child of 1989 is the most important document on children’s rights, and has also been a law of the Greek state for almost thirty years (Law 2101/1992).

The Convention recognizes the right of children to education and establishes the prohibition of discrimination against children. In addition, the Convention stipulates that refugee children should enjoy all the rights that other children have.

But what is outlined by the Convention is far from reality. According to a recent announcement by the “Teachers’ Initiative for the Right of Refugees and Immigrants to School,” since schools officially opened this year, most children have not attended for a single day.

On the islands in the Aegean, which host refugee populations, the situation is even worse.

Access to public education is essentially nonexistent, and school registration at the Reception and Education Centers for Refugees for this year was only just completed recently. Thus, the only alternative is ‘non-formal’ schools, such as LEDU and KEDU run by NGO Arsis on Leros and Kos.

How many children are currently detained at PROKEKA on Kos? No one seems to be able to say for sure. Solomon contacted the Ministry of Migration and Asylum as well as the Hellenic Police, asking for information about the number of children there, and the average length of stay in detention, but we did not receive a response.

“At least let us leave”

“My dreams for my children are for them to go to school, to feel like human beings, and to be safe. I want them to be able to understand people,” Hamam Widad, the mother of Jamal, told Solomon.

She herself is happy that her child’s drawing has traveled far beyond where they are. “But I would like to feel this joy and be somewhere else, not trapped here,” she says.

It remains unknown when Widad, Jamal, Hala, and Yasif will be able to live outside the barbed wire which has kept them trapped for the past five months.

The same uncertainty characterizes the future of even more people who seek refuge in Europe. In the new center on Kos, which is likely to be a closed center, construction work is progressing at a very fast pace, on a parcel of land which is far larger in relation to the existing structure.

As the construction of reception centers provides for the creation of spaces such as a restaurant and school, it is estimated that this closed center will be the exclusive residence of asylum seekers on the island.

Thus, all people who arrive in Kos and apply for asylum are expected to essentially live in detention – under the same conditions that Widad and her children are experiencing today.