Converting enthusiasm into a well-rounded story

Substance abuse. Drunk boys, harming themselves, other boys, or the care workers. Smashed windows. Dead rats. Could these things have taken place in Moria?

Substance abuse. Drunk boys, harming themselves, other boys, or the care workers. Smashed windows. Dead rats. Could these things have taken place in Moria?

Hello there,

This is Stavros Malichudis, reporter for Solomon, and I’m very much excited about writing this first “Notes from the field” newsletter for you!

After a year of working closely with one another, my colleagues at Solomon now know that when I get hold of something that could possibly make a powerful story for publication, I get overrun by enthusiasm.

It usually starts when I get a lead for a new story, or just finish an appointment with a source who has shared something I find extraordinary. And, then, things usually go like this: me spamming my coworkers with messages or calls about it, making promises that this time I will have a 3,000-word piece ready for publication in two days (even though nobody asked me to), and then they try to calm me down, weighing things and sharing concerns and many hmm’s.

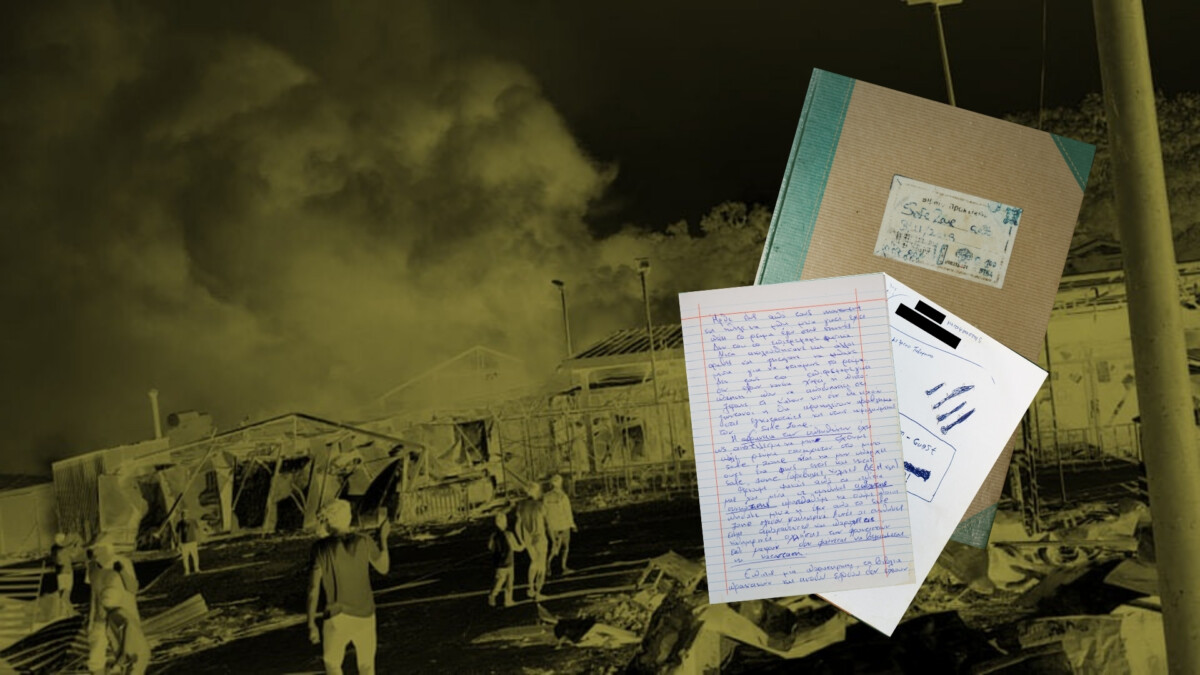

So, as you can imagine, this was also more or less what happened, when I found myself walking around the ashes of Moria, among burnt tents and destroyed possessions, and I stumbled upon an IOM’s personnel logbook from the safe zone of Moria’s Reception and Identification Center that became the basis for the powerful story we worked on, in collaboration with Investigate Europe and Reporters United (and published also in Tagesspiegel, Mediapart, Publico, openDemocracy, Klassekampen, WP Magazyn, Vice Deutsch, and infoLibre).

Thankfully we didn’t publish the story “within a week”, as I had initially insisted to my colleague Iliana Papangeli, when I got back from Lesvos and we started working on it together. We published it approximately 1.5 months later, on November 1. And, to be honest, it couldn’t have been done otherwise.

Here, I would like to share with you how we spent that time, and all the steps we followed so that a notebook that contained original material – which we considered to be of major importance not only for Greek but for a European audience – took shape into a well-rounded story.

Okay, so a logbook is in our possession now, its hardcover reads “safe zone 2019”, and its pages seem to refer to shocking events that minors endured while living inside a “safe zone”.

(“Safe zones” are separate areas in Greek refugee camps, where unaccompanied minors live under supervision, for their safety).

But how could we prove the logbook’s authenticity and the fact that it refers to the safe zone of Moria, and not that of another camp?

The first issue might seem like a totally stupid question; why would someone fill a 190-page notebook with made-up events, which include a number of different characters? It was still a question that needed an answer though.

Here’s what we did first, but it only led us to dead ends:

One of the first things that Iliana did was to transcribe all the logs into a Word document. This way, we could both have simultaneous access to its content, as well as search for patterns, for possible connections between specific events or persons mentioned, and get a better understanding on all different aspects. We also prepared an English translation for our colleagues at Investigate Europe and Reporters United.

One of the first things that Iliana did was to transcribe all the logs into a Word document. This way, we could both have simultaneous access to its content, as well as search for patterns, for possible connections between specific events or persons mentioned, and get a better understanding on all different aspects. We also prepared an English translation for our colleagues at Investigate Europe and Reporters United.

We had reported from Moria before and knew individuals that had lived there as unaccompanied minors themselves. We arranged to meet with one of them in Athens, (we’ll call him “X”) where he lives now.

Substance abuse. Drunk boys, harming themselves, other boys, or the care workers. Smashed windows. Dead rats. Could these things have taken place in Moria? Our contact, “X”, laughs – these things couldn’t describe any other place but Moria.

But there was a more important point. When we showed “X” the logbook, and started reading some of the names of the minors involved in incidents, after just hearing two or three names, he said he knew one of them.

In fact, not only did he confirm to us that he knew that boy, but he took his mobile out of his pocket and showed us a picture of the two of them among other boys, on Lesvos.

A few days after, we also managed to track down one of the three employees who had signed the logs with their full names. Although they did not want to talk at all about their work (something we fully respected), the answers they provided confirmed they worked there at the time.

That meant we were good to go.

On October 15, two weeks before the piece was published, we contacted IOM. Besides asking for comments on major issues mentioned in the logs (e.g. substance abuse by the minors, allegations of rape, fears of electrocution due to exposed wires/outlets), we asked whether they could confirm that the three aforementioned care workers were employed by them, in the camp at that time (ensuring them we would fully protect all personal data).

Αlthough ΙΟΜ did respond to most of our inquiries, (putting the blame on Greek authorities), nowhere in their reply did they mention the three employees, or the logbook at all, despite our persistence.

“Acknowledging your sincere intention to protect personal data, IOM is not in a position to confirm the names or the authenticity of any document, which remains at your disposal,” was their answer. We found that interesting, and would love to hear your thoughts on that.

The employee of IOM that we managed to track down for this report seemed to really be committed to his job, and to have a real interest for the wellbeing of minors in their care. So why did they not want to talk to us for this report?

One thing worth keeping in mind, is that employees of UNHCR, IOM as well as many NGOs sign non-disclosure agreements that prevent them from talking to the press.

This, as well as fear that they could possibly lose their job, if it was revealed that they talked with a journalist, has for the past years in fact made a number of well-informed people unwilling to share the info they have, not even in vital cases – we have witnessed this happening even in cases of sexual abuse.

Both for us and our colleagues at IE and RU, it was vital to protect the anonymity of everyone mentioned in this story, both minors and personnel. Here is how we did that:

And then, we were ready to share the pictures and the transcription of the logs with our media partners. This way, their anonymity was not only secured from the potential readers of the story, but even from the other journalists and editors that worked on the story for the different media partners.

One of the very first things we did when we started working on this story was to contact the Ministry of Migration & Asylum. We contacted them repeatedly by phone and email, and we were told that they were working “at this very moment” on our requests.

But they missed the first deadline we set, they missed the extended one, and in the end they simply did not answer at all.

However, that’s nothing new.

In journalism, we often talk about terms like “accountability” of the authorities, and others like “open governance”, “access to data”, etc. But, something that any person living outside of the Greek reality should keep in mind, in terms of how these materialize in our reporting process, is that authorities here, whether it’s the Ministry of Migration & Asylum, the Army or a local authority, don’t feel any sense of obligation to provide journalists (or citizens) with information on issues that they consider strictly as “theirs”.

These different entities share a common view on the data they are asked to provide, as if it’s something strictly personal, like a personal belonging that is stored in their pocket.

When foreign colleagues ask us what’s the best way to contact press officers (e.g. from a Ministry), and we explain to them that it doesn’t really matter, because it doesn’t really make any difference, they wonder: “But they should answer! Are they not worried by the journalists? Don’t they realize that not answering will make them seem even worse?”

Well, there’s a short and a long answer. The short one is NO.

The long one is that, in a country that produces more unpleasant news than it could possibly consume, they know that the best they can do is let it flow, not keep it on the surface with a comment, and the next day everyone will be talking about something else. Or, alternatively, they will keep you on hold for weeks, and then they will send some irrelevant and publicly available file that you already had, and will then consider their job done.

I’d like to be fair – this has been the case with previous governments as well. But, to be honest, never before have I experienced a Ministry, to which I have been directing requests for various reports for a full year, and they have not even once provided a reply, or even one statement, consisting of a sentence, of a phrase, or even two words.

That is something new, and it has happened since the new government came into power.

Hope you liked this letter. I’d love to hear from you and please feel free to share your thoughts, feedback or suggestions.

You’ll be hearing from me more often from now on.

‘Till next time,

Stavros

Before you go, can you chip in?

Quality journalism is not of no cost. If you think what we do is important, please consider donating and becoming a reader who makes our work possible.