Born on January 1st

An unpublished piece from earlier this year that attempts to explain a common and noticeable phenomenon that we often encounter in our coverage of refugees.

An unpublished piece from earlier this year that attempts to explain a common and noticeable phenomenon that we often encounter in our coverage of refugees.

Hello there,

In this “Notes from the field”, we – liana Papangeli, Stavros Malichudis and with our colleague Nasruddin Nizami’s contribution – share an unpublished piece from earlier this year that attempts to explain a common and noticeable phenomenon that we often encounter in our coverage of refugees.

Every year on January 1st, Nasruddin Nizami, our colleague here at Solomon, gets on social media to send wishes and greetings to his loved ones.

As the COVID-19 restrictions are still in force throughout Greece, and citizens are instructed to avoid gatherings, he exchanged even more online messages this year. But, amid wishes for a happy new year, Nasruddin also responds to the notifications from a particularly long list of Facebook friends’ birthdays.

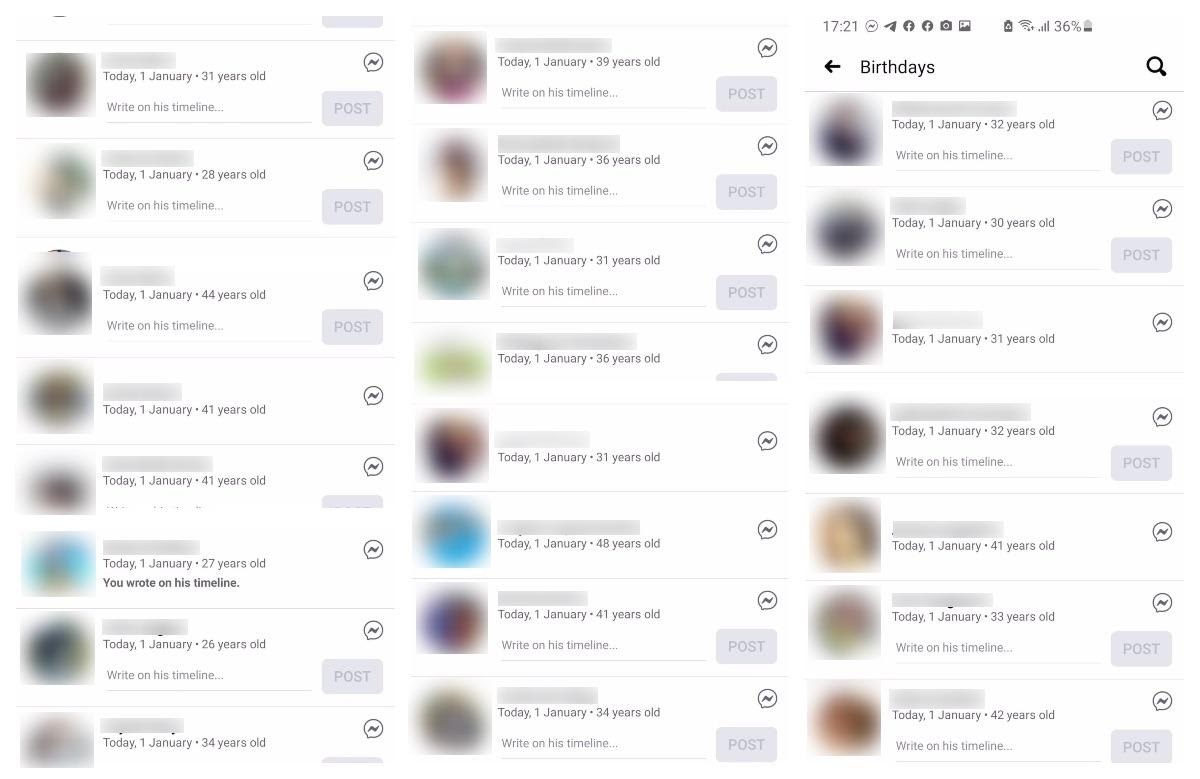

Here is just a glimpse of what his Facebook feed looked like on January 1st:

Nasruddin was born in Afghanistan, has also lived in Pakistan, and has been employed in the humanitarian sector for many years now. As a result, many of his Facebook friends have a refugee background and dozens ―regardless if they live in Greece, in other European countries, back in his home country, or Pakistan― appear to have their birthdays on the first day of the new year.

But it’s not because of pure coincidence, rather there are specific reasons for it.

“First of all, it’s the war,” Nasruddin says. “The war has destroyed everything.”

During the last 50 years, Afghanistan and its citizens have suffered through wars and conflicts. The invasion from the Soviets in 1979 was followed by the involvement of the US in 1986, and the withdrawal of the Soviets two years later, in 1988.

During these decades, as The Independent reports, the government didn’t have a system in place to register births, so “families saw no reason to record the exact dates.” What was enough for people to get by, was an approximate birthday on the Islamic calendar.

In 2001, the US Army invaded Afghanistan and, for the last twenty years, things haven’t improved. By 2019, Afghanistan was considered the most dangerous country in the world, and the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan recorded more than 10,000 civilian casualties ― for the sixth year in a row.

Today, young people in Afghanistan are reportedly keeping notes in their pockets when they leave their house in an effort to ensure that, if they die, their relatives will be able to identify their bodies. In such conditions, it’s understandably difficult for documentation to be kept.

A second reason lies in the fact that a lot of mothers do not give birth in hospitals, but at home, so there are often no official documents that would include a date of birth.

“Most of the people in Afghanistan don’t actually have a birth certificate, so in turn, this is also why they have no specific birthday,” said Ali, an asylum seeker from Afghanistan who lives on Lesvos in Greece.

“Regarding celebration of birthdays, the new generations might do something like cake or celebrations. Or perhaps some rich and high-level families. But most of the people do not celebrate their birthday.”

Then, equally important to the two aforementioned reasons lies the third factor, that both Nasruddin and Ali highlight.

A significant percentage of the approximately 38 million that live in Afghanistan today are illiterate. In 2020, it was reported that over 10 million youth and adults in Afghanistan were illiterate, while the adult (15+) literacy rate, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, refers to 43% of the population throughout the country.

“It’s not uncommon in many cases for both the mother and the father of a newborn baby to be illiterate,” said Nasruddin.

When we texted her to ask her view on this, Sajida, a 20-year-old asylum seeker from Afghanistan that currently lives in the new camp of Kara Tepe on Lesvos, responded back with laughing emojis.

“That’s right,” she said. “Many people don’t know their exact date of birth, my parents included for example. And my birthday, officially, is on the 1st of January.”

Sajida’s case is somewhat different, but not uncommon among the Afghan population seeking refuge in Europe. Like Nasruddin, Sajida also spent a large part of her previous life in Pakistan, where she lived for 18 years.

“In my case, we could say that it is due to a mistake that took place already when I was a refugee there. During the registration of the refugees, the workers there were used to putting the wrong date of birth on their documents, and they also very often wrote their names wrong!”

One day Sajida asked her parents when was the date of her birth. They told her they had written it on a paper as a reminder, but later lost it.

So, the most accurate answer she has been able to get as to when her birthday is, so far is “at the beginning of the winter season”.

Greece lies some 5,500 km west of Afghanistan, but one might be surprised to learn that the reality of inaccurate birth dates is not that alien to the reality of the past decades in Greece.

For instance, when our parents (today around their 60s) were born, it was also common in Greece, in a large number of cases, for mothers to give birth at home and not at a hospital.

When their parents went to register the birth in the following days, the dates recorded on their birth certificates are often somewhat different than the actual date of birth. For example, someone might have been born on March 10, and have March 13 as the official date of birth on their documents.

In these cases, the date that they would celebrate their birthdays as they grew older would be the former.

For children who were born in December, in the Greek countryside, it was common to wait until January and then officially register the newborn babies. This way, the parents thought, they could go to school one year later, more mature and better prepared for it.

Asylum seekers from Afghanistan are not the only ones who often have January 1st as a birthday on their documents. So is the case with citizens of other war-torn countries, like Syrians, Iraqis, Somalians, Sudanese, Ethiopians, and Vietnamese.

Like in Afghanistan, in a number of these countries birthdays are not celebrated each year, thus making it more difficult to keep a record of when someone’s birth date is.

Besides the instances where asylum seekers do not know their exact birth date, and choose January 1st, as it’s the easiest one to remember, this date is also typically attributed by authorities when they can’t verify someone’s date of birth through documents.

This is often the case in Greece and includes equally men, women, or minors (often unaccompanied).

This is the situation in other countries also. On New Year’s day of 2017, the UK Refugee Council wished a happy birthday to “all refugees who don’t know or can’t prove when their real birthday is and have been assigned January 1st instead”.

Based on immigration data from 2009 in the US, Business Insider reported that 11,000 of the nearly 80,000 refugees in the US that year had listed January 1 as their birth date. And sometimes, January 1st can be the date of birth for all the members of a refugee family.

Before you go, can you chip in?

Quality journalism is not of no cost. If you think what we do is important, please consider donating and becoming a reader who makes our work possible.