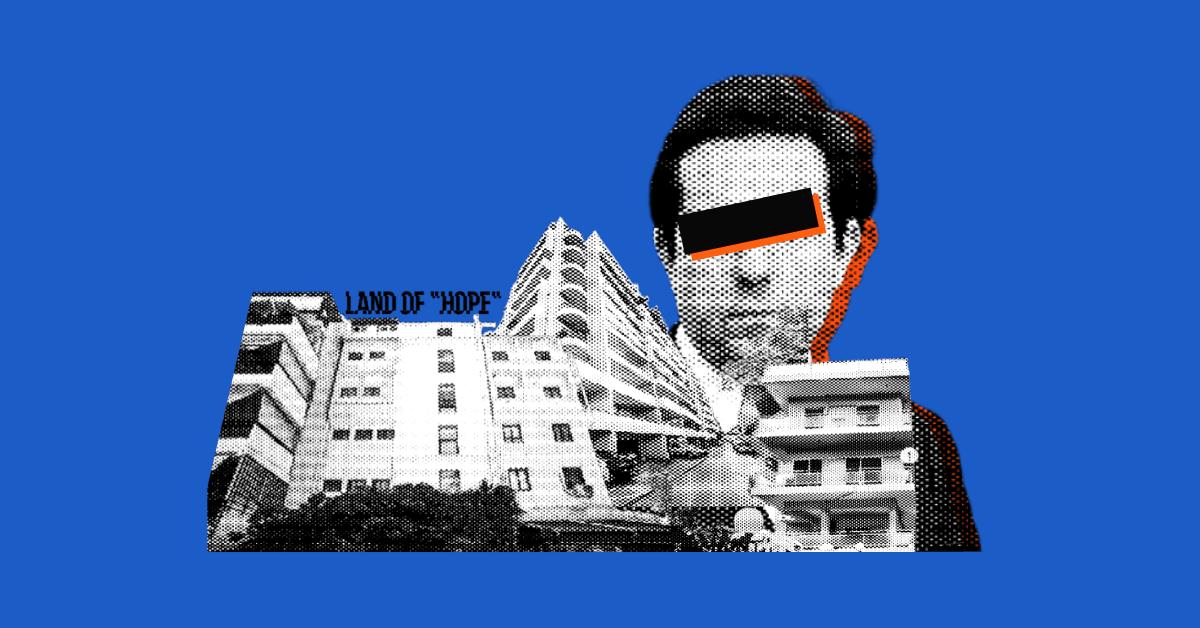

This is the site of an abandoned factory facing the port of Patras, Greece’s ‘Gate to the West’ and the country’s third largest city. Patras is situated in the northern Peloponnese, 215 km west of Athens.

On January 13, the day this picture was taken and sent to us, 40 to 50 refugees and migrants from Afghanistan and Iran, all men and boys, many under 18, were living there in makeshift tents under collapsing roofs and dripping water.

Everyday, they wait for the right moment (usually after dark) to try to sneak under a truck or inside a large shipping container that will be loaded onto a ferry to Italy.

In about five hours from the time of writing these lines, and after already five days of failed attempts, M., a 17-year-old boy from Afghanistan, one of the dozens of refugees and migrants who have camped at the factory, will try to hide on one of the vehicles in the port, hoping that this time he’ll make it.

In previous days, the port police had spotted him along with others before they could make it to the ferry. They were chased and beaten.

This is M.’s first time in Patras. But it’s not his first attempt to leave Greece.

The day we first met, December 1, 2020, in Athens, M. had been living on the street for two weeks.

After having spent 11 months at a hotel for unaccompanied minors in Athens, he decided to leave and try to cross the border to Italy from Igoumenitsa port in north-west Greece. The friends he was with managed to cross the border. But he didn’t.

After two failed attempts in Igoumenitsa, he returned to Athens to seek refuge at the hotel he had stayed at before, but he was not accepted. So he decided to try his luck once again, and attempt to cross the border. The third time he came closer to his goal than any other previous attempts. He managed to hide underneath a truck but before the vehicle was loaded on the boat he was spotted by a police dog and caught by the officers.

His fourth attempt had a similar ending, although he had adhered to the smuggler’s instructions. Only this time the police sent him back to Athens and then the COVID-19 pandemic began and he stopped trying. Only temporarily at least.

The route from Patras is not new

As we have previously reported, the port of Patras has served as a major gateway for migrants, mainly from Albania, since the early 1990s.

In the mid-1990s, the first Kurds arrived in the area and a few years later Iraqis, Afghans and Somalians followed, among other ethnicities.

After 2015, and particularly with the closure in 2016 of the Balkan route and the EU-Turkey agreement, the passage from Greece to Italy has become appealing again and has attracted thousands of migrants and refugees who attempt to smuggle themselves onto ferries by hiding under trucks.

Back in 2007, our very own colleague Nasruddin Nizami tried to take the similar route from Patras to Italy. Here is his testimony:

“I was in Patras in October 2007. I was living in the makeshift refugee camp at the old port. There were thousands of people trying to leave everyday, but the police would catch us and then we had to try again the next day. I spent a whole month trying, until one day I made it hidden underneath a truck which was loaded on another truck. It wasn’t easy. Actually, it was very dangerous. There were people seriously injured and the chasing between the police and the refugees had led, in cases, to the death of the latter ones […] I had to pay a smuggler and follow his instructions. There was no other way. It didn’t matter if you could make it alone. In fact, if you would try this, it could have really bad consequences. Even if you would have survived the beating from the police, you would most likely be stabbed by the smugglers. The mafia rules there and it’s not something you can just skip.”

Why refugees and migrants want to leave Greece

M. is not the only asylum seeker we met during our reporting in the past few weeks, who is now trying (or has already managed) to leave Greece.

Of the young asylum seekers from our Moria’s missing migrants December report, one is also in Patras, trying to hide on a truck every evening; another one just recently made it to Serbia and has plans to advance north.

Last week, Greek photo-journalist Giorgos Moutafis uploaded a short video on Facebook while reporting algonside the migrants stranded in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The video by Moutafis, a colleague we respect for his ethical, on-the-ground reporting, is divided into short (10-20 second) clips where he asks migrants, (that in some cases have spent years in Greece, before deciding to try their luck in another country) where they lived before.

In their responses, one can notice a wide representation of the realities that are often in store for people on the move in Greece, whether they are recognized refugees or undocumented migrants.

In broken Greek, which they have learnt through everyday work and not school or integration classes, they respond: they have harvested strawberries in Manolada; they have picked oranges in Argos; they have worked in the orange groves in Skala, Lakonias.

Despite having lived in different regions, they share the same reasons for leaving: no papers, no insurance, no prospect for the future.

Greece might have recently appointed a deputy migration minister (rather ambiguous, having called the migrants “unarmed intruders” in the past), who is specifically tasked with integration, but the truth is that neither this nor the previous government showed interest in the true integration of people seeking refuge in its land; whether this was social, cultural, or professional.

In fact, during a meeting with our Solomon media lab students, when asked when Greece did the most for the integration of incoming populations, our guest speaker professor of Political Science and History and former president of the Federation of Human Rights, Dimitris Christopoulos, said this was actually… in 1923, for the incoming refugees from Asia Minor.

During the past weeks, we have been delving into the professional realities of asylum seekers arriving in Greece, and will soon publish two Q&As that we believe touch upon crucial issues.

Apostolos Kapsalis, a researcher for the Labor Institute of the Greek Confederation of Labor and post-doc researcher at the Department of Social Policy, Panteion University, shares with us his experience and view of having extensively researched the migrant land workers in Greece.

And Paul Schlang, a freelance researcher and author of An Abundance of Unleashed Potential, a recently published study on refugee labor market integration in Greece, discusses the findings and insights of his research with us.

The two Q&As will be followed by a longread which aims to present different, both good and bad, practices from various regions in the country.

“Hope seeing you in another country”

If we were to make a prediction about how things will progress from now on, based on our research of the past weeks, we would say that things don’t look promising.

There is not much data available; we don’t know what percentage of asylum seekers arriving in Greece manage to find legal employment, what their professions or backgrounds are, and therefore how they could benefit from fair access to the labor market and how society could benefit from their skills (and the state from their taxes).

No matter if they attain international protection, in terms of employment, asylum seekers seem to be limited to the informal market and are subject to labor exploitation and don’t really have the opportunity to settle in.

In that sense, it’s not unexpected that migrants will continue on to other countries, hoping that they can get what they need – mostly papers – sooner. As M. wrote to us in a goodbye message before getting ready for his attempt of the day: “Hope seeing you in another country”.

*We use the initial of the Afghan teenager’s first name in order to protect his privacy.