The slogan Prima gli italiani sounds quite similar to Donald Trump’s “America first.” The phrase Italia agli italiani (Italy for Italians) is also a popular refrain of the neo-fascist movement. With these words, Lega, a nationalist right-wing party, is leading the polls in Italy, ahead of the European Parliament elections.

Lega’s leader, Matteo Salvini, is the current Minister of the Interior but many Italians believe he will soon lead the entire government. In the previous elections Lega rallied 17% of the vote and according to latest polls he is expected to get about 30%. It is expected that in the upcoming European elections, Lega will be the first among the Italian parties in the next European Parliament.

Since its formation in 1991 to 2018, the party was known as Lega Nord and for years it was known as a territorial political entity with a precise target: the secession of the Northern regions from Italy, or at least a high degree of self-government and fiscal autonomy.

Its members and voters were used to insulting people from Southern Italy by employing a wide range of stereotypes: in their speeches, they referred to southern Italians as terroni (a derogatory nickname) and as people who are unwilling to work, people who live off the Northerners and always try to take advantage of others. However, when Matteo Salvini was chosen as the new leader, he imposed a radical change both in the party’s name and attitude.

Lega’s Sicilian candidate in the next European Parliament, Angelo Attaguile, was one of the first to believe in the project of a national party. “I am in favor of regional self-governments and I saw Lega Nord as a solution to many problems here. My duty has been to bring their attention to Southern Italian issues,” he says.

In the beginning, many people were hostile to a party that blamed and insulted others. But, little by little, the new Lega became the symbol of sovereignty and nationalism, gaining endorsements in Southern Italy as well. “We got 5% in Sicily in the last elections and I expect we will have better results in the European ones, which can be a turning point for us. Now, when I ask people to vote for me, saying I am running for Lega, they are favorable: Italians are intelligent and can overcome the past,” explains Attaguile.

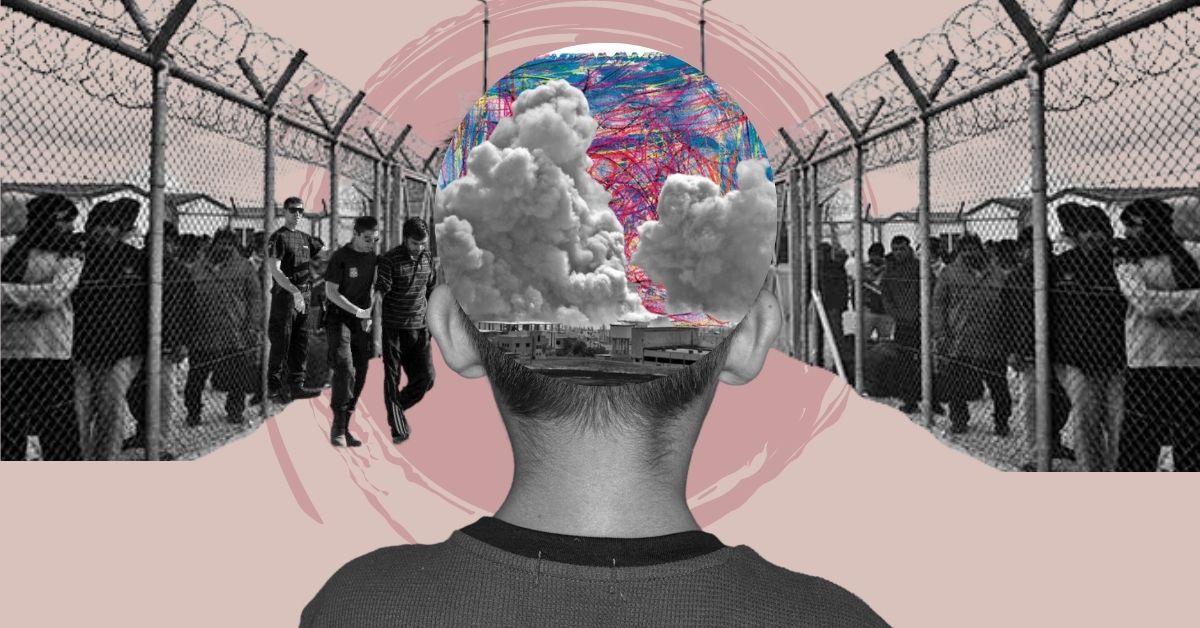

One of Lega’s most used tactics is the “battle” against refugees, a communication strategy which seems to speak to the electorate. “The immigration issue is a priority for us, as we have been victims of an uncontrolled invasion. Migrants are creating many perils: we are not against those people, we criticize the previous accommodation and reception policies.”

However, their attitude towards migrants is quite similar to how Lega Nord once viewed the Southern Italians. But Attaguile refuses a comparison: “At that time, I, as Sicilian, was bothered by some comments. Nonetheless, it was just a matter of chauvinism. Man’s natural tendency is to defend what you have and to reject the other.”

“Legitimizing” racism

The inclusion of Southern voters is just one of the paradoxes related to Lega’s growth. This party’s members often appeal to what they call “traditional Christian values” but indeed they seem to pick and choose which ones.

Lega is strongly against same-sex marriage and adoption for homosexual couples, but they criticize the Pope when he says refugees should be welcomed. Lega constantly seeks to convey the idea that migrants are a danger to society and a source of trouble for the Italians. Like Attaguile, Salvini usually uses the term “invasion” referring to arrivals by sea, although the number of arrivals has dropped significantly: 779 people reached Italy by boat in the first four months of 2019 (9.467 in the same period in 2018 and 37.235 in 2017).

Nonetheless, perception seems to have more influence than real data: “Lega’s propaganda and media are overstating migrant’s presence. So the average person is still thinking ‘we cannot take in everyone,’” says Alfonso Di Stefano, director of Rete Antirazzista Catanese (Catania’s anti-racist network), a citizen’s association that promotes solidarity initiatives for migrants.

In Di Stefano’s opinion, Salvini’s rhetoric incites xenophobic feelings and racist behaviors: “In Catania, I saw a driver insulting a migrant who wanted to wash his car window. After a shouting match, he got out of the car and ran after the migrant with a tire iron in his hand.”

Salvini’s key role in the Italian government is seen as a form of “legitimizing” aggressive instincts towards foreigners. “Before he was nominated Minister of the Interior, nobody openly claimed to be racist. Now there are some people who see racism as evidence of their superiority and pride themselves for this. It is a devastating consequence of Matteo Salvini as a political figure.”

Lega’s propaganda has also tried to criminalize all the NGOs which save migrants in the Mediterranean Sea. Salvini and his followers label organizations such as Open Arms or Sea-Watch “accomplices of human smugglers.”

“In past years residents used to help refugees: when a boat arrived, it was common for people to bring food and clothes or to pass the hat to enable them to travel. Now the first thing people do is call the police,” Di Stefano states.

Xenophobia on the rise

Silvia Di Meo is a young member of Borderline Sicilia Onlus, a small non-profit founded in 2008 in order to report the facts about immigration in Italy’s southernmost regions. She has been gathering reports of racist incidents since June 2018, when the new government took office, and has been comparing the data to similar events which occurred in 2017. Although her research is still ongoing, she will probably detect an increase in racial attacks, including both verbal and actual violence. “I was struck by the high rate of these incidents in the local newspapers,” she states.

Some stories she tells are shocking: “In November 2018, a 19-year-old Ethiopian woman arrived in Italy by boat after giving birth in a Libyan camp. The baby was admitted to the hospital in Ragusa, but when the mother came to visit, the other new mothers in the hospital complained of her presence, claiming that she was carrying disease.”

Many migrants have been threatened, insulted or beaten in recent months. Di Meo classifies every assault related to racial discrimination: “In some instances, racism is not the reason to attack, but there are still some discriminatory behaviors or words.”

Italians who help migrants are also a target. “I Girasoli is a non-profit organization which takes care of migrant families in Sutera, a small mountain village in central Sicily. Their bus was burned – a clear and threatening message.”

According to Di Meo, xenophobic content is also spreading fast through the internet, as many people do not want to go in depth with actual facts. Hateful attitudes are like gasoline for Lega’s engine: the party wants to spread the idea that solidarity toward migrants itself is a crime against Italians.

The role of “the Beast”

The growth of Lega would not have been so fast without the very skillful use of social networks, which have promoted and boosted its leader. Matteo Salvini has a personal team which is in charge of managing his social media accounts.

Bestia (the beast) is the name of this team, whose activity is funded by the state, ever since the leader of Lega became Minister of the Interior. According to investigative magazine L’Espresso, this is costing the government more or less €1,000 per day. This is of no financial cost to Salvini, and he’s gained a lot in terms of popularity: 3.6 million fans on Facebook (he is the first among Italian politicians), 1.4 million followers on Instagram and 1.1 million on Twitter. Thanks to social networks, Salvini can share short and simple messages, avoiding complex reasonings.

Luca Morisi, the head of Bestia, is a recognized expert in this field. He coined the nickname Il Capitano (The Captain) for Salvini: he makes the people believe they’re part of a big victorious soccer team, often a trump card with Italian voters (in 1994 Silvio Berlusconi called his new party Forza Italia, basically a phrase which serves as a sort of hymn to soccer fans).

Salvini is involved in a never-ending election campaign, which he manages by using catchy slogans such as #nonmollo (I don’t give up) or #portichiusi (closed harbors) when he comments on the news about refugees. His aim is to simplify every statement as much as possible, no matter if it doesn’t correspond to reality. For instance, he calls all the people who are on a boat sailing towards Italy clandestini (a term for “illegal migrants”), regardless of their right to seek asylum.

Another point of Salvini’s propaganda is strictly related to his public image: Lega’s leader wants to show that he’s the average next-door neighbor. He often prefers wearing sweaters instead of suits and he loves posting pictures of his breakfast, which includes Nutella. It should sound funny, but it’s a very subtle strategy to pose as an “ordinary man” fighting against old-style politicians, heartless economists and detached-from-reality intellectuals.

Last but not least, it is very important that the name of Salvini appears everywhere, all the time: The Italian Minister of the Interior has posted his opinion on football matches, the winner of a music festival, a popular tv-show, and even Valentine’s Day. His enormous popularity makes every statement relevant for online newspapers. Therefore, even the media which is against Lega, publishes content related to something Matteo Salvini has said every week. His rise on the web seems to be unstoppable.

A dehumanized society

“How can a good Christian vote for Salvini?” wonders Mimmo Lucano, mayor of Riace, a village in Southern Italy which for years has been a model of good reception towards refugees. Lucano is under investigation for the facilitation of illegal immigration and his office has been suspended.

For many people, he is the victim of a political trial: Lucano is “guilty” of protecting the most vulnerable people and promoting an integration model which has been studied and adopted as Europe’s refugee crisis increases. Incriminating him is a way to destroy a message of peaceful coexistence.

During a conference in Cinisi, near Palermo, Lucano said what he has repeated several times across Italy: “Salvini helped to create a climate of hatred and division in this country. Nowadays, a dehumanized political scenario seems to prevail. He is leading us to a society without human values. And we cannot let that happen.”