Even though they theoretically enjoy full access to the labor market, refugees in Greece are usually drawn to the informal labor market and remain excluded from their labor rights and their full integration into society.

This is one of the main findings of a recent study on refugee labor integration by Faros, a humanitarian organisation that provides humanitarian care and individual support to unaccompanied children and refugee youth in Greece, published in collaboration with the MIT D-Lab last December.

The report, “An Abundance of Unleashed Potential” on labor market integration of refugee youth in the Greek labor market, examines, among other things, the legal and political framework in Greece, as well as the difficulties that refugees face in their efforts to find job opportunities.

On the occasion of Solomon’s ongoing research on the realities of employment opportunities for refugees and migrants in Greece and the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, we spoke with Paul Ferdinand Schlag, lead researcher and author of the study.

Paul Schlag began his research in Greece, utilizing his experience and approach from a similar study he had conducted in 2019. As part of his dissertation, he had examined entrepreneurship among Syrian refugees in the provincial regions of Lebanon, on the border with Syria.

“I faced many difficulties in Lebanon,” he tells us. In addition to the mass demonstrations demanding the removal of the old political order that coincided with his time there, making it difficult for him to travel to the region, he was confronted with the distrust of the people.

“The first time I went to talk to people I had a Lebanese friend with me. Syrian refugee business owners noticed that he spoke with an accent, worried that he might be associated with the government, and were afraid to speak freely.” The next time he returned with another friend, a Syrian refugee, and only then did people begin to open up to him.

The difficulties he faced in Greece had to do, firstly, with the access to reliable, filtered data. Secondly, with the gradual increase of coronavirus cases in the country, which led to measures such as lock-downs, and made him change some of his research plans.

“An Abundance of Unleashed Potential” draws on the experience of multiple stakeholders in Greece and provides essential insights into the missed opportunities and the potential of refugee youth.

Most importantly, however, is that this new situation caused by the pandemic led to another important finding: COVID-19 is also proving to be the “disease of inequality” when it comes to refugee and migrant labor.

Given your experience in Lebanon, what were your expectations when you started your research in Greece? And what were your first impressions when you arrived?

The situation in Lebanon was very tough on the Syrians. The revolution broke out, partly because of this huge financial crisis in the country. There was a lot of hardship, especially in the rural communities far off the grid. There were mothers with small children, and homeless on the street, of which nobody took care of.

So, after seeing this really bad situation in Lebanon, I was expecting there would be much more support for refugees in Greece, which turned out to be correct.

And I think this was my first impression. That there are a lot of organizations working with refugees, which was an absolute difference. I would say I was also surprised by the level of support that was given by governmental actors in some situations.

I was impressed first of all that, back then, there was a [simple_tooltip content=’Lefteris Papagiannakis was Vice Mayor on Migrant and Refugee Affairs of the Municipality of Athens from March 2016 to August 2019.’]vice-mayor for refugee affairs[/simple_tooltip] in Athens, and also talking to him, to UNHCR personnel, and to the Ministry of Migration and Asylum, I was impressed by how well informed these people were and how good their intentions were.

And that made me hopeful, I would say. On the other hand, in Lebanon, you have to neglect this refugee issue completely. I was talking to someone from UNHCR in Lebanon, and was pitching him this idea that I could write my thesis on how building up their businesses can help refugees integrate. He told me that, generally, the proposal was fine but we would have to cut out the integration part. That there is no option for refugees to integrate there, the Lebanese society won’t allow it.

So you have this first contact with all these stakeholders, with organizations and state factors. When you went deeper into your research, did you encounter these good intentions in practice as well?

Well, on the practical level, there were a couple of things that held back refugees’ integration into the labor market and society. I could share two things, especially as small anecdotes.

The first one was that most job counselors that I talked with said that the administrative barriers are just too large for refugees to bridge alone. So it’s very difficult for them to navigate the space. And this can be, for example, registering for an AFM (tax number) where one job counselor mentioned that, when refugees want to register for an AFM, they have to fill out a form, which is only available in Greek. So there are these very, I would say, obvious barriers, that you don’t really understand why they exist, because they seem so obvious.

And another one is that it is very difficult for these people to understand what their rights are. There is the example of opening a bank account, there are reports of banks refusing the opening of bank accounts for refugees. If you are new in a country, and you are not sure about the workings of the society, it takes a lot of understanding local initiative to push for your rights, and a lot of courage because it’s difficult on a practical level.

The practical workings are very complex, and it will probably take time to be adapted because this is also a specialty of Greek society. Even for migrants from, say, the UK or France, it is difficult to work around these processes. And naturally, the process is the same or even more difficult for refugees. So it’s expected that this will be a barrier.

Shouldn’t such issues have been solved by now? Back in 2015, or 2016, maybe the bank wasn’t aware asylum seekers can open bank accounts. But in 2018, or 2020, and now in 2021, shouldn’t there be some advance on this?

Yes, technically there should probably be one. I think that the difficulties for the Greek government on the refugee issue are taking place on so many different topics, so I would give it the benefit of the doubt and just think that these small procedural steps are simply overlooked.

There are NGOs reporting such issues to the government and making them aware of them, but I think there also needs to have some grassroots reporting on this. And this is, for example, why a report like that is really good because it highlights these things. And because I am not entirely sure whether the government by itself would be aware of these topics, if they’re not reported from the bottom up.

Can you tell us about how your report was conducted?

We did interviews with actors who are involved in the process around refugee integration, NGOs and government stakeholders, and also some companies. We also did secondary research and checked some of the analysis that had been done before.

Taking all these into account, we tried to combine the insights that all of these methods provided, and tried to answer the main question on how NGOs can improve the labor market and integration of refugees.

How was your experience in terms of access to data, on issues that you researched?

When querying all these databases in Greece, I realized that they are pretty extensive, but the statistics do not filter for refugees. And that can be really annoying.

They filter for third country nationals, but third country nationals are refugees, if they are registered, but also these international Google employees or people working for NGOs. So all of these statistics can’t really be used. Maybe you can do it, if you have all the background information. But as a first query it would be much easier if there was a filtering option, not only third country nationals, but refugees too. But maybe that’s just too tricky to do.

What are some of the findings that you would like to highlight, that you found most interesting during your research?

The first one is that, oftentimes, the improvement of the labor market integration can be a very long process. Because the people that arrive in Greece, maybe 18 or 20 years old, are not immediately ready to be hired by someone, even though they might have the skills.

They might be, for example, very good barbers or skilled in some other profession, but they need to be granted some time to adapt to the Greek society, maybe learn a little Greek, and have some support on a psychosocial level. And this means that it needs to be NGOs who take care of these people, and not only focus on the refugees that can enter into employment immediately.

This was my first takeaway in this report: that to build an environment where refugees can integrate into the labor market, it’s very important that not every NGO focuses exclusively on their hiring quota. I think NGOs are already aware of this, but I wanted to point that out anyway.

What were some of the different positions that you encountered in terms of this issue?

As an example, there are the NGOs providing computer science or coding classes that manage pretty well to get their beneficiaries into employment afterward. But they pre-select who will be enrolled in their courses. And they ensure this consistent participation, through tests by which people can at some point even be required to leave the course.

So it’s logical that their hiring quotas are higher in the end. Then, on the other hand, you have NGOs like Faros that have opened doors for everyone. Sometimes for kids who don’t speak Greek at all, only very little English. And, naturally, that means that the hiring quota might not be as high.

But both play a role in providing an environment for employment. Because if you don’t take care of the people who need psychosocial support now, you will not have the people who can be employed five years from now.

And what would be a second issue that you would like to highlight?

The second one is a pretty obvious one: that the Greek language is the most important teaching of all. Whatever you do, there needs to be a Greek language component. And people need to be made aware that it’s really important to study Greek if you want to integrate in Greece.

That’s not really different in Germany either: it’s also important to learn German if you want to stay in the country. We did a very small survey on this, which unfortunately we couldn’t extend because of the pandemic. But we found a split in whether refugees wanted to stay in Greece, or how long they wanted to stay in Greece, and which language they prefer to learn.

What you would naturally assume is that if someone wants to stay in Greece for three, four, or more years, they would also be aware that the first language they should then learn is Greek. But in our survey, this correlation was not present.

Do you have an explanation as to why this phenomenon occurs, why they prefer to learn English? Is it maybe that they think that after a few years they might be able to leave Greece? Is the language too difficult?

I would say that it’s obvious that learning English is very attractive to anyone, anywhere in the world, because it opens up the path into high skilled employment, this international employment possibly for multinational corporations.

So, maybe that would be a reason. But besides this, one big learning in the survey for me was also that, generally, people seem to like Greece. I myself have some context with refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan in Germany. And this country is really not the promised land: you know that you have to learn, you have to work, and pay a lot of taxes. It’s usually a little cold and the summers are short. This is what my refugee friends tell me. It’s not perfect, just like no other country is perfect.

But maybe Greece is just a little closer to them, this is what I observed. From the climate to the construction of the buildings. At some points when I was driving through the city, I didn’t really see a difference between Beirut or Athens.

And what’s maybe a third issue that you would like to highlight?

I want to highlight the last one, especially because some NGOs might read this interview. It is the opportunity of social cooperative enterprises, which are offered as a legal form of an enterprise, and are targeted towards integration.

This makes it much easier to create a company, when sole focus has to be the integration of the beneficiaries into Greek society. I was surprised that this concept isn’t more well known.

You also mentioned that in Lebanon asylum seekers could be self-employed, but this can’t be the case here. In Greece, asylum seekers can only work as employees, hired by someone else.

Well, this was forbidden in Lebanon as well, but there was really nobody checking on this there. There is a lot of bribery going on so people will do it. And, they invest surprising amounts of money into building shops that are illegal and without having the required permits, or sometimes they get the permits after having already opened the shop.

Syrian shops are usually in poorer areas in the outskirts of Beirut, and of course the bordering area to Syria, where they also build their own communities. They are usually very close to other Syrian shops, and hide inside alleys rather than on the big streets.

Here in Greece, did you meet refugees who are entrepreneurs?

I actually talked to only one person who was a refugee in Athens and had some entrepreneurial project going on.

We were looking for refugees who had built a business, because this was one perspective that we wanted to highlight, but we couldn’t find any except for this one person who was a special case because he spoke very good English, he also spoke Greek, and was extremely engaged in various other projects. He had founded his own radio show for example. So in a way, he seemed like an outlier.

This is one thing that we run into in this report. Entrepreneurship is a buzzword used quite often. But you have to look behind this concept. And, really, the basic necessities to have entrepreneurship as a pathway forward are not there in Greece. It’s one of the worst countries to do business in.

And this is for Greeks, who speak Greek and are accustomed to this whole culture. Entrepreneurship for refugees is not really feasible. And it is even a little frustrating because in the national integration strategy, entrepreneurship is mentioned as one of the main pillars of refugee integration.

Philippe Leclerc, the UNHCR Representative in Greece, wrote the introduction to your report. And he mentions that if the Greek society and the Greek labor market come together, they can integrate the people arriving here. What is your impression, are they working towards that direction?

Generally speaking, concerning the openness of people and the willingness to help that I experienced, there’s absolutely a human capacity to make this work.

My personal belief, though, is that there’s usually enough for everyone, just economically speaking. The question is never whether one disadvantaged group is taking something from the other disadvantaged group. Although this is the dynamic that first arises.

There’s enough for everyone, it’s just a question of how you distribute it. And this is very clear for me in Germany, I guess it’s also very clear in countries like the United States where this inequality is just staggering. In terms of Greece, I can’t really judge because I’m just not well enough informed also about the cultural factors. But my gut feeling is that this question of whether society can integrate a weak group, which is also not huge in numbers, it’s probably the wrong question.

We would also like to discuss the consequences of the pandemic. What were your findings regarding how COVID-19 has affected refugees in Greece?

During our research project, the impact on COVID-19 was not as big as I personally expected. Most organizations that I talked to were coping quite well, so COVID-19 did not take up a lot of space in our interviews.

But you have to keep in mind that this was in summer, when the overall situation was easier. I’m not really sure how it is now, with the second wave.

One finding, though, that we did make concerning the experiences of refugees in the lockdown was that, especially for women, it was very difficult. And this was because they have two responsibilities: the responsibility for the safety of the family and the responsibility for taking care of the children who were not going to nursery or school.

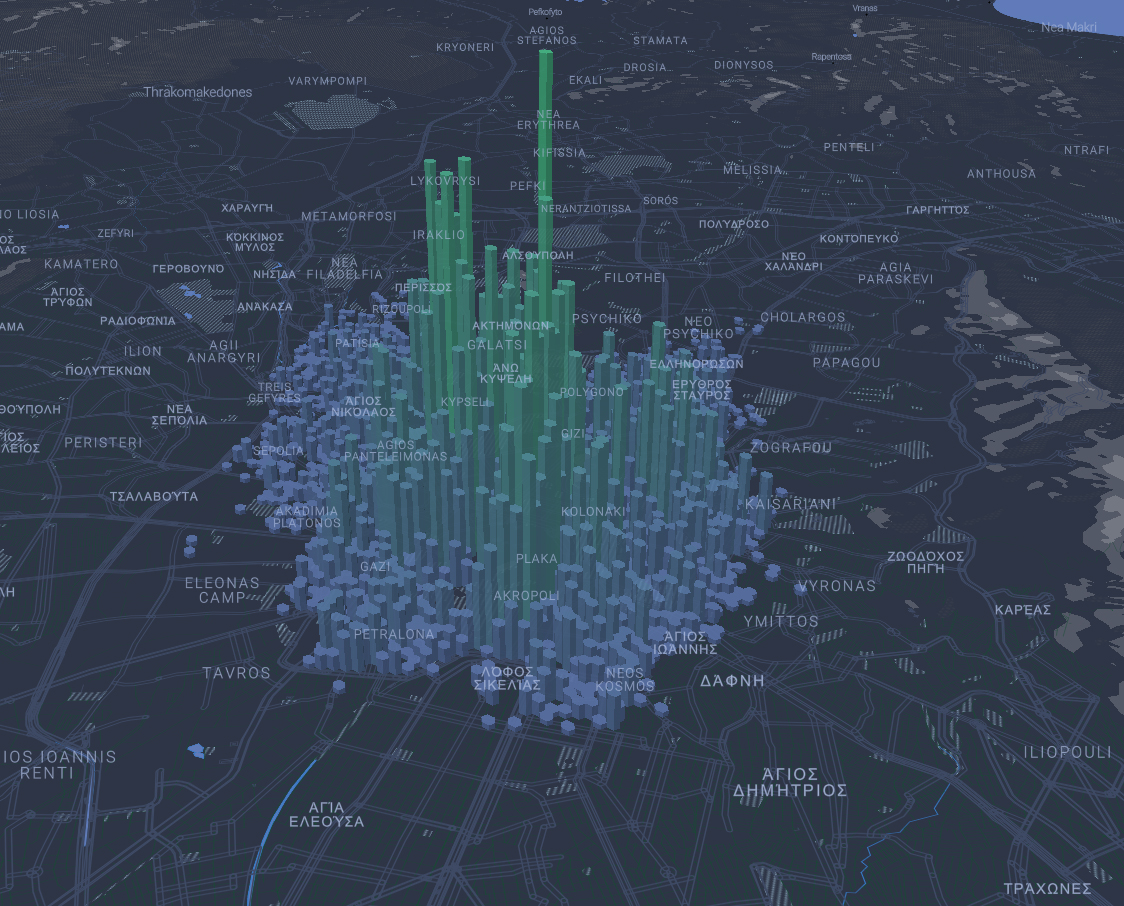

Then, of course, we did some research on the informal economy around the area of Acharnon, in the center of Athens. We observed Afghan teenagers, maybe 17-18 years old, not having a contract, not being paid very well. Also being in a lock-in situation, because they were working 16 hours a day, seven days a week, which takes away any opportunity to look for alternatives and live alternative life paths.

Thinking of all the people we met back in summer, who worked in the hospitality sector and restaurants and in these small kava places (liquor stores), I don’t think these people are in work anymore.

Just one last question from us. If you could take this research and the findings further, what would be interesting to focus on and explore more?

We covered the NGOs and actors working on labor market integration, so my next step would be to cover more in detail the refugees themselves. I think that having these structured, but deep conversations with the people affected, makes it so much easier to understand what should be done.

But another perspective, that is not really highlighted in this report here, would also be to go in more detail on the societal dynamics, and to have more of an exchange with the Greek population. Not only the ones that do humanitarian work, but decidedly the population that might not be on the side of integrating refugees.

I would invest some time in understanding what drives them, what their worries are. And maybe try and find out how we can build a bridge between people like that and the refugees seeking integration.

This Interview is part of Solomon’s project “Migrant workers in Greece in the time of COVID-19 ″ and is supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Office in Greece.