Distance-hating

Can you hate someone you don't even know? Sociologists and media researchers whose work focuses on Poland, have been surprised in recent years to find that the country has one of the highest rates of Islamophobia in Europe.

Can you hate someone you don't even know? Sociologists and media researchers whose work focuses on Poland, have been surprised in recent years to find that the country has one of the highest rates of Islamophobia in Europe.

“I don’t think they should come here, to a small village where the crime rate is zero. The way they act and the situation we see, what’s happening in…”, says a woman from Methoni, Pieria, on camera, without managing to finish her statement.

“How do they act? What is it that bothers you about their behavior?” the reporters and panel members ask.

“The crimes they commit,” she answers.

“What crimes? What crimes exactly?”

“What you talk about on the news bulletins: rape, whatever happens, theft and so on,” the woman replies. And she repeats: “What you report on the news bulletins.”

As of last Wednesday morning, the excerpt above from the show “Good Morning Greece” hosted by Giorgos Papadakis, was widely shared on social media. Some commented and emphasized the fact that immediately after this exchange, the host went to commercials.

Others commented on the truth that they say is hidden within the woman’s statement: “Well, first you tell us that they’re raping, stealing, and so on, and then you wag your finger at us because we don’t want them living here.”

Can you hate someone you don’t even know? Sociologists and media researchers whose work focuses on Poland, have been surprised in recent years to find that the country has one of the highest rates of Islamophobia in Europe.

How can this happen in a country where Muslim citizens are barely perceptible in the public sphere? In Poland, Muslims make up just 0.1% of the total population, in a country of 38 million people, an estimated 35,000-45,000.

It is worth noting that, in a 2015 survey, only one in ten citizens (12%) appear to know a Muslim personally. However, despite the lack of direct contact, the feelings towards Muslims have a certain reaction.

In a 2011 survey, almost one in two Poles (47%) believed that there were too many Muslims in the country, while 59% of young Poles (18-24), even though they had no contact with Islam, believed Islam is dangerous.

To record the unprecedented situation in the country, researchers had to come up with a new term: “Islamophobia without Muslims.”

Methoni Pieria is a seaside village with fewer than a thousand residents, many of whom may not have come into contact at all with refugees who have been or have passed through the country in recent years.

The woman who was interviewed on TV, however, speaks with certainty about specific behaviors that will occur if “those people” arrive in her area: rape, theft, and so on. Where does the information come from? The brief answer is, from the media.

Across Europe, studies on how mass media functions, reveal that Muslims are stereotypically portrayed and mostly represented in a negative light. In the case of the Greek media, it is not difficult to see that this phenomenon is present in their reporting.

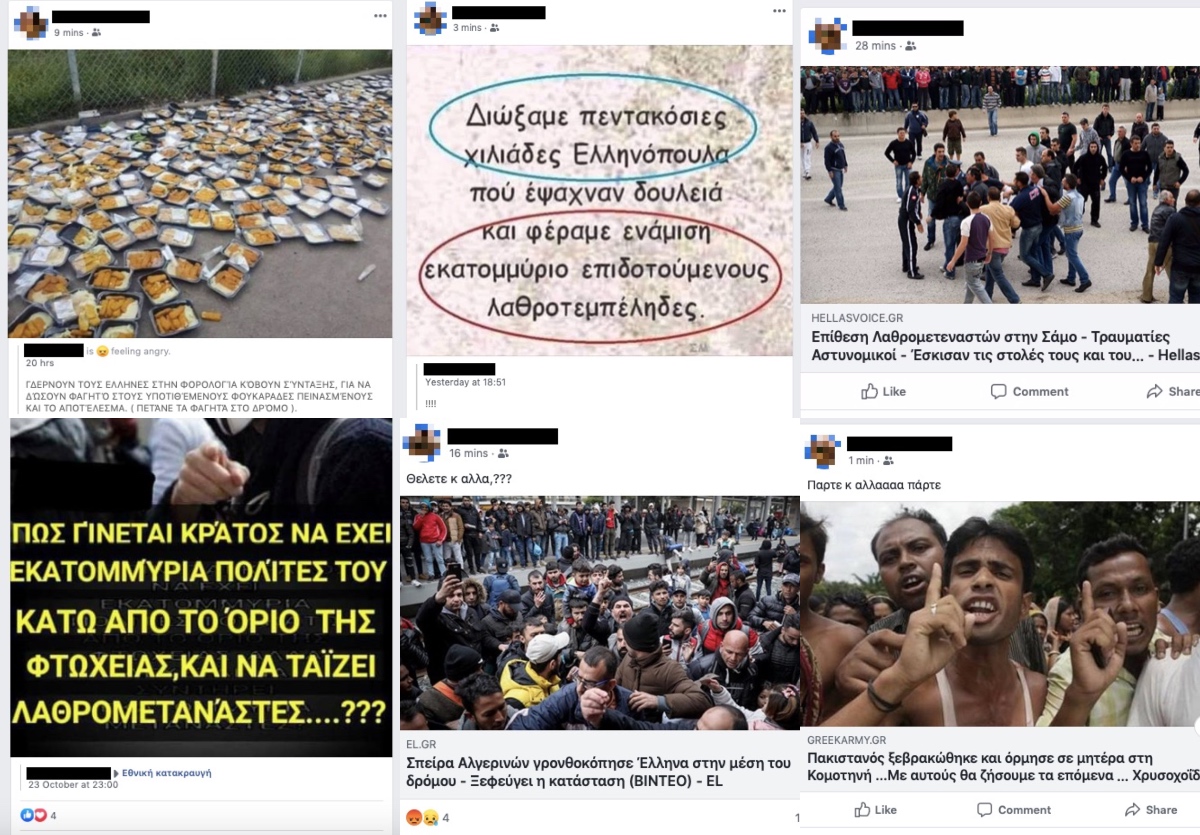

But more than that, social media also plays a significant role, as users spend quite a lot of time creating a buzz, using certain pages and accounts and becoming deeply immersed – while alternative representations of reality are on the decline. Here’s what a typical day on Facebook looks like for someone exposed to far-right propaganda.

Is this something that can be addressed? The example of the recent outburst of hatred by former footballer Alexis Alexandris leaves no room for optimism: if for so many years, the same lies about the refugee issue are still being reported as fact, it is clear that something has gone very wrong.

Both the previous and current governments, as well as large international organizations present in Greece (some often advise their European employees to come and work in Greece, but to avoid areas where refugees live or frequent), have failed to communicate to the public what the reality is, and have not tried to bridge the gap between the two sides, or listen to the real concerns of the Greeks.

So, at a time when conferences about countering fake news are taking place one after another, (and sometimes to the benefit of the organizers instead of to the issue at hand), in a room in Oreokastro or in a living room in Giannitsa, people watch tele-marketing shows hosted by the head of a political party, or scroll through Facebook and are still exposed to every kind of fake news which manipulates their most humble fears.

If there’s one thing that offers some kind of hope, it’s that, despite the lack of real information, the phenomenon of racist outbursts does not seem to correspond to the majority. As Giorgos Tsiakalos, professor of Education at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki, rightly pointed out, in Giannitsa and Serres, Skydra and Naoussa, in Kilkis and Vrasna, it was not the residents in their entirety, who prevented the arrival of refugees in their areas.

It was just some residents. In reality, these residents represent a small and insignificant minority. They just shout a lot, and loudly.

Before you go, can you chip in?

Quality journalism is not of no cost. If you think what we do is important, please consider donating and becoming a reader who makes our work possible.